CONTACT: Timothy Smeeding, smeeding@lafollette.wisc.edu, (608) 890-1317

MADISON—University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers found discouraging results in the latest Wisconsin poverty analysis using a state-specific measure.

The overall statewide poverty rate using the Wisconsin Poverty Measure (WPM) rose from 10.2 percent in 2017 to 10.6 percent in 2018, staying above the 2015 rate of 9.7 percent (the lowest WPM rate since measurement began). These findings were released this week in the Twelfth Annual Wisconsin Poverty Report by Timothy Smeeding, Lee Rainwater Distinguished Professor of Public Affairs and Economics at the La Follette School of Public Affairs and Affiliate and former Director of the Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP), in collaboration with IRP Senior Programmer Analyst Katherine Thornton.

This rate increase suggests that progress against poverty in Wisconsin since the Great Recession has stalled. The COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on the state’s economy may further jeopardize progress against poverty.

“The Wisconsin Poverty Project grew out of an effort to assess the economic toll of the Great Recession. Now, the upheaval brought by the COVID-19 pandemic is having an unprecedented impact on the economic well-being of Wisconsin communities. We don’t yet have data for 2020, but the report can offer us insights into how policies have reduced poverty in our state in the past and provide an important point of comparison to what we can learn in upcoming years,” said Katherine Magnuson, Director of the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Particularly concerning in the 2018 data is that poverty rose for both children and the elderly. According to the WPM, child poverty rose from 10.1 percent in 2017 to 11.1 percent in 2018. Poverty for older Wisconsin residents (aged 65+) also increased slightly from 2017 to 2018 (from 9.5 to 9.7 percent), continuing a climb from a low of 7.8 percent in 2015.

Smeeding notes, “Despite increased income from work in 2018, families had less money after taking into account taxes and work expenses, even when public benefits were included in the calculation. Increasing payroll taxes and falling income supports reduced the safety net’s ability to pull Wisconsin households out of poverty. The rising costs of childcare and medical expenses contributed to higher poverty for both children and the elderly in 2018. Nine years or more into a long term recovery of jobs, we should have seen better poverty outcomes.”

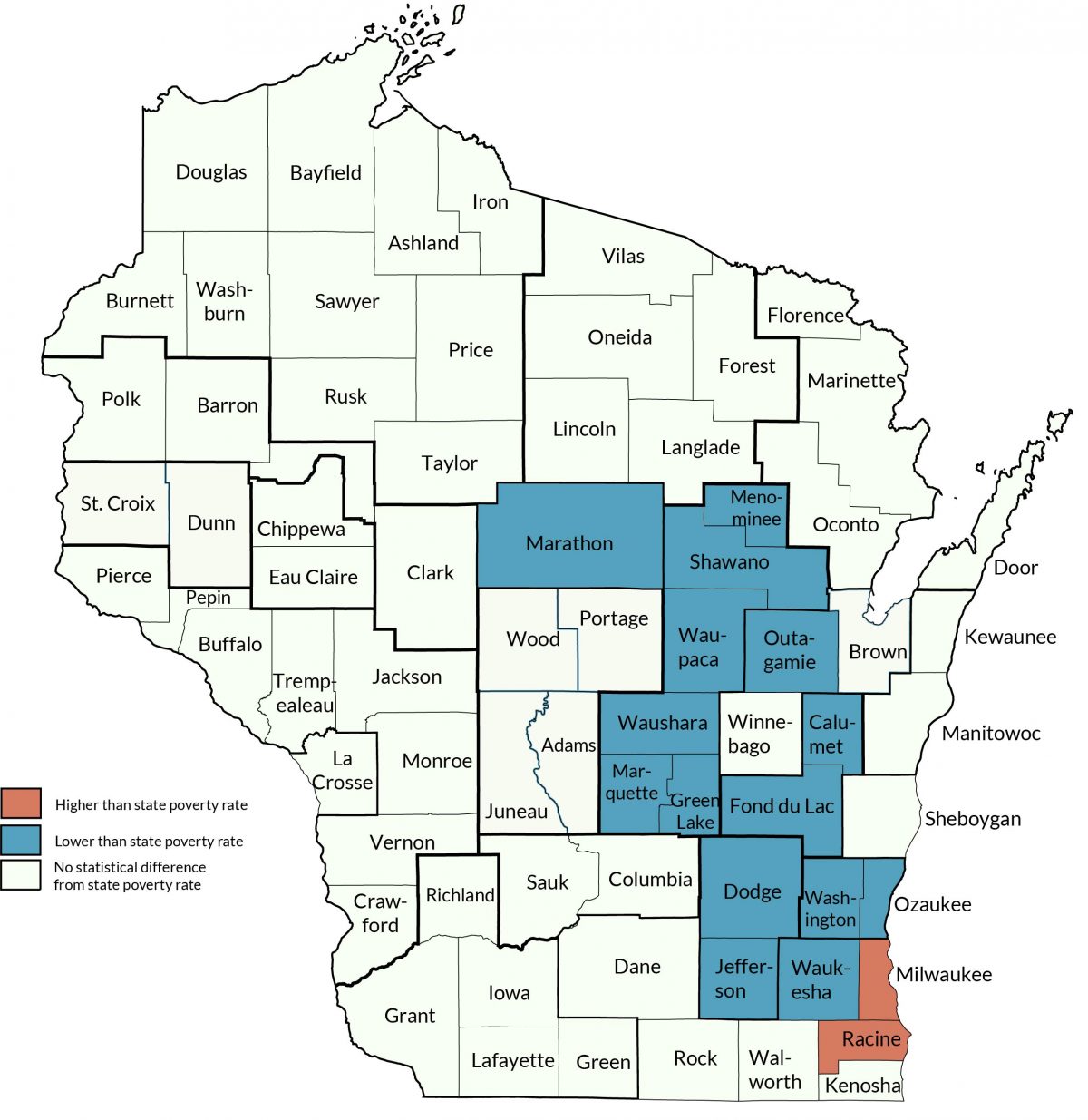

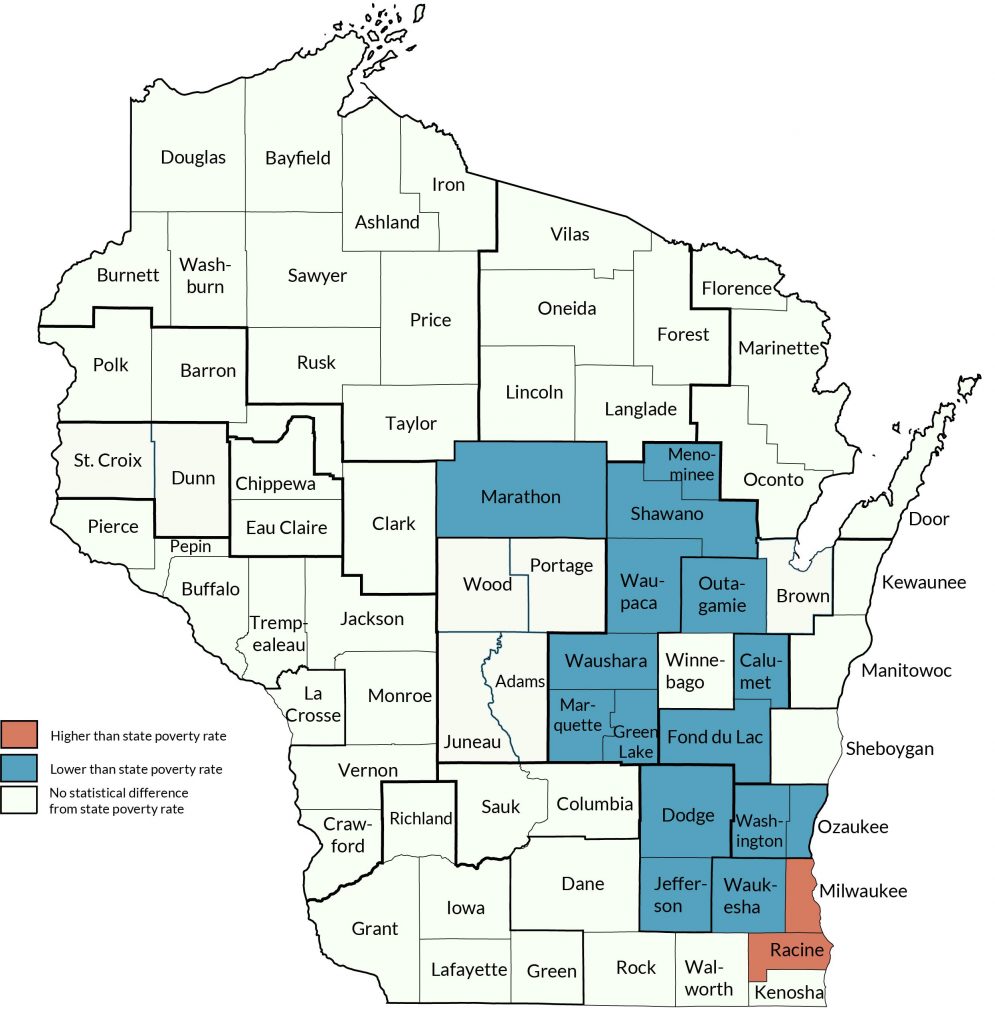

Source: Institute for Research on Poverty tabulations using 2018 American Community Survey public use data.

Milwaukee and Racine counties had the highest poverty rates (16.2 percent and 14.2 percent respectively). All other areas in the state either had rates similar to or lower than the state average of 10.6 percent (see map). Due to small sample sizes, some counties were grouped into multicounty areas. While rates were as low as 4.0 percent in some counties, it’s important to note that there can be significant variation in poverty at more localized levels within counties or across multicounty areas.

The report suggests that if we are to make progress against poverty for the non-elderly, work alone at today’s wages is not enough. Greater work and income supports are also needed. The report goes on to say that we need to maintain and improve the safety net, reduce childcare costs, and raise Wisconsin’s minimum wage to more than $10 per hour if we are to see meaningful change in poverty rates.

Brad Paul, Executive Director of the Wisconsin Community Action Program Association (WISCAP), which supports the Wisconsin Poverty Report, commented, “WISCAP is proud to support the Wisconsin Poverty Project, which shares University of Wisconsin’s expertise in this important way, so we can all have an accurate accounting of poverty among Wisconsinites—and therefore be better equipped to fight it.”