- August 2023

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 62-2023

Education and employment are key factors in promoting economic stability. As young people reach adulthood, most either enroll in postsecondary education, become employed, or do both. According to 2018 data, nearly 9 in 10 youth are “connected” in this way, but that leaves 11% of youth overall who are “disconnected,” that is, not engaged in further education or employment. Those percentages are much higher for some racial/ethnic groups (e.g., 23.4% for Native American youth and 17.4% for Black youth) and for young people from low-income backgrounds.[1]

Connectedness Among Young Adults with Foster Care Experience

Emerging adults benefit from connections with formal and informal mentors who can guide and advise them through transitions to adulthood. But youth who have spent time in foster care often have weaker connections to kin and community as a result of being removed from their networks, which can compound the impacts that disconnection has on their overall well-being.

Young adults with foster care histories are especially vulnerable to disconnection from employment and further education, with as many as one third of those young people disconnected at age 21.[2] This trend continues as former foster youth age, with one study finding that slightly less than half were employed at age 25–26, compared to about 70% of their peers who had not been in foster care.[3]

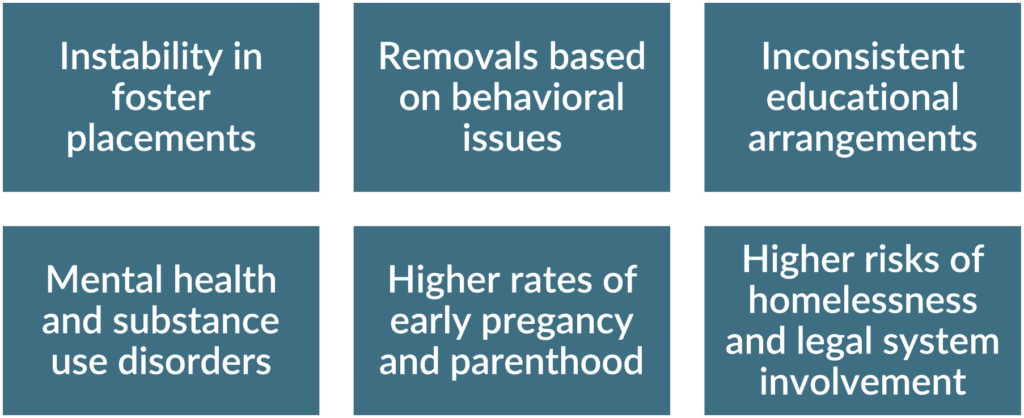

Youth in foster care are more likely to experience a variety of conditions that can make pursuing stable employment and further education more difficult than for their non-care-involved peers. While these factors can vary by demographic features like race and ethnicity, gender, and disability, foster youth transitioning to adulthood and independence can be more likely to face several significant challenges, including:

Policy initiatives at the federal level—like the 1999 Foster Care Independence Act (FCIA), its 2001 expansion, and the 2008 Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act—have given states a blueprint and funds to support foster youth during the critical transition to adulthood. But scant research uses national data to examine different types of programs on the success and stability of former foster youth.

“I was lucky enough to stay in the same foster home throughout high school, when I began living with them in the beginning of high school they were like, ‘Hey, this is preparing you for college, keep that in the back of your mind for everything you do because things you do today will kind of influence what is about to happen in the next few years.’”[4]

Recent research by Jennifer Geiger and Nathanael Okpych uses data from the National Youth in Transitions Database (NYTD) to assess various state-level interventions, the rates of youth who participate in them when available, how it affects their likelihood of being connected to work or school, and what that means for stability and success in early adulthood.[5] Their work provides important insights by looking at both employment and education simultaneously, which offers a more nuanced perspective than just whether youth are in school or not, or employed or not.

Assessing the Effects of Extended Foster Care

Extended Foster Care (EFC) expands foster care benefits from age 18 to 21. This policy emerged through the 2008 Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act, one of the most significant policy developments in recent decades. Nearly all states and U.S. territories now offer some form of EFC coverage to youth in care at 18, provided they meet some basic qualifications related to continuing education, employment, or workforce training programs.[6]

Extended Foster Care (EFC) expands foster care benefits from age 18 to 21. This policy emerged through the 2008 Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act, one of the most significant policy developments in recent decades. Nearly all states and U.S. territories now offer some form of EFC coverage to youth in care at 18, provided they meet some basic qualifications related to continuing education, employment, or workforce training programs.[6]

EFC services may include academic supports, career preparation and employment training, and mentoring and counseling accessible up to age 21. This builds on the 1999 Foster Care Independence Act (FCIA) and its 2001 expansion provisions for independent living services (IL) and education and training vouchers (ETV) that provide direct support to foster youth on the cusp of adult self-sufficiency.

In addition to the NYTD data, interviews conducted at ages 17 and 21 with a cohort of nearly 8,000 foster youth beginning in 2014 provide context for the numbers. Results from Geiger and Okpych by the age-21 interview are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Protective, Risk, and State-Level Factors for Former Foster Youth, by Age 21.

|

Protective Factors

|

| 69% of the youth were “connected,” that is, working (41.4%), going to school (11.5%), or both (16.5%) |

| Career preparation services were the most utilized support (50.3%), followed by post-secondary educational services (43.1%), education aid (34.6%), and employment or vocation training (34%) |

| Youth who at age 17 were employed, enrolled, or had finished high school or earned a GED were more likely to be connected at age 21 than their peers |

|

Risk Factors

|

| Youth who are parents at age 17 are no less likely than their peers to be connected, although they are less likely to be both working and enrolled |

| Past involvement with the criminal legal system, substance or alcohol issues, or foster placement due to behavioral issues all put youth at a higher risk of being disconnected |

|

State-Level Factors

|

| Less than half (47%) lived in a state that provided a state college tuition waiver to all (40.6%) or some (6.4%) former foster youth |

| Overall, youth who spent less time in foster care before the age of 18, had fewer foster care episodes, had more placement stability, or exiting foster care through adoption or guardianship were more connected and had better outcomes than their peers who differed in those conditions |

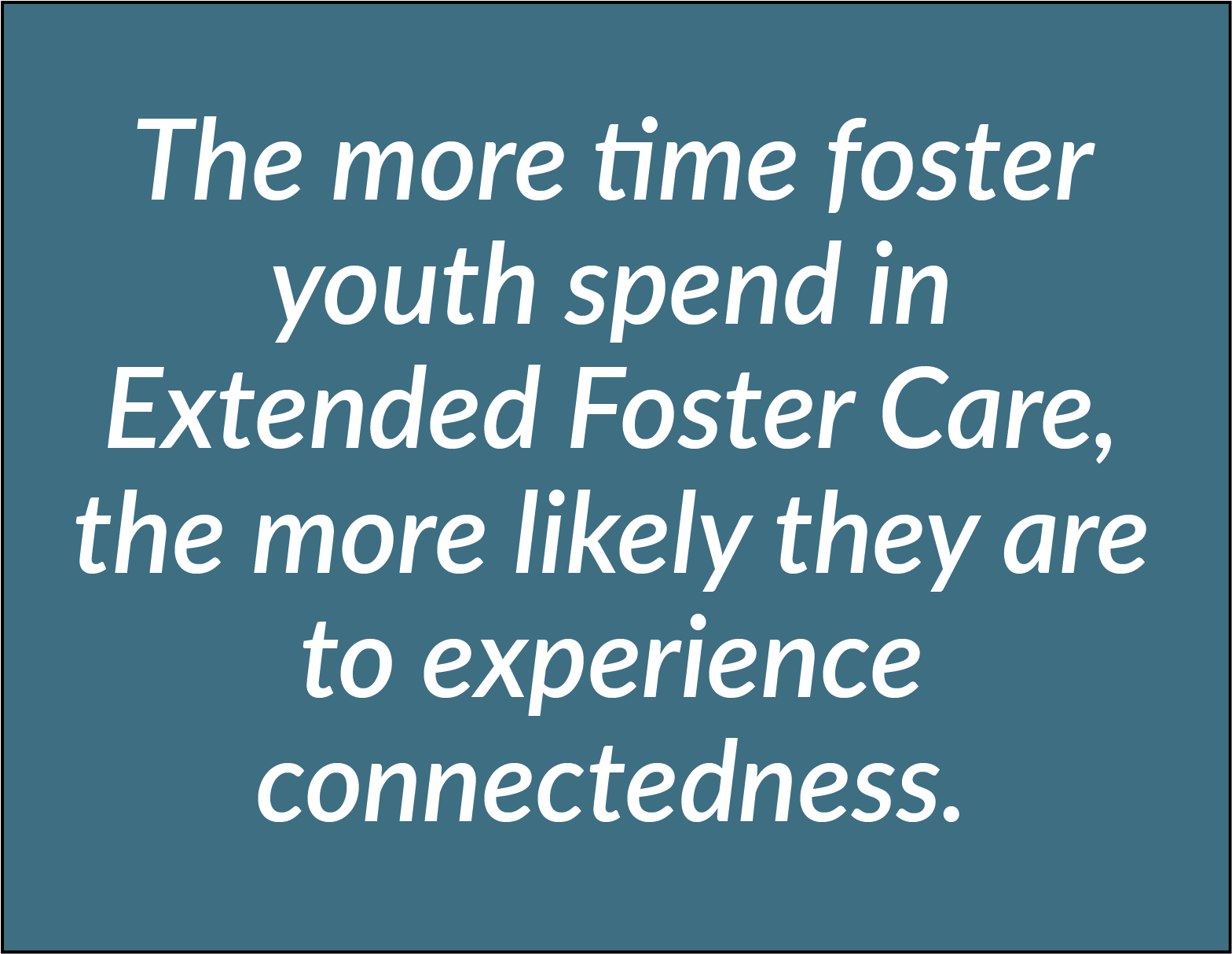

| Youth who spent more time in extended foster care had higher rates of connectedness, but simply living in a state with EFC did not make a difference |

| Few state-level policies show a significant impact on whether former foster youth are connected or not at age 21, with the exception of state tuition waivers when they are available and accessible to all foster youth |

“Since I was in the foster care system, I applied for the [child welfare] scholarship. So, I get $511 a month and they pay for my books and the only thing I have to pay for is my room and board, so that’s exciting.”[7]

Policy and Practice Implications

There are proven policy and practice approaches that can enhance connectedness and stability among young adults with foster care experience as they transition to adulthood.

- Ensure that tuition waivers available to all foster youth regardless of state of residence and creating pathways for assistance to successfully access those programs. Tuition waivers should be provided apart from other aid such as Pell Grants, works-study funds, etc. rather than being used to “top off” other forms of financial aid.

- Encourage holistic coordination between child welfare agencies, schools, and employers to develop and implement programs serving foster youth.

- Prioritize programs to enhance placement stability for foster youth, which can improve connectedness through linking employment and education.

- Maximize the relatively high rate at which foster youth receive career preparation services by increasing access, expanding training opportunities, promoting supportive relationships and mentoring, and analyzing data generated to increase programmatic effectiveness.

- Nurture youth’s skills and interests through exposure to higher educational possibilities, apprenticeships and internships to gain marketable job skills, and training for educational or employment success. These interventions are best started early for foster youth since they often lack the typical familial and community networks of non-foster youth.

Compiled and edited by Judith Siers-Poisson, IRP Communications Director, with editorial and design support from James T. Spartz, Nateya Taylor, and Dawn Duren.

This research was funded in part by the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

[1]Lewis K. (2020). A decade undone: Youth disconnection in the age of coronavirus. Measure of America, Social Science Research Council. https://measureofamerica.org/youth-disconnection-2020/

[2]Courtney M. E., Okpych N. J., Park K., Harty J., Feng H., Torres-Garcia A., Sayed S. (2018b). Findings from the California youth transitions to adulthood study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of youth at age 21. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. https://www.chapinhall.org/wp-content/uploads/CY_YT_RE0518_1.pdf

[3]Okpych N. J., Courtney M. E. (2014). Does education pay for youth formerly in foster care? Comparison of employment outcomes with a national sample. Children and Youth Services Review, 43, 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.04.013

[4]Avant, D. W., Miller-Ott, A. E., & Houston, D. M. (2021). “I Needed to Aim Higher:” Former Foster Youths’ Pathways to College Success. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30, 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01892-1

[5]Geiger, J. M., & Okpych, N. J. (2022). Connected After Care: Youth Characteristics, Policy, and Programs Associated With Postsecondary Education and Employment for Youth With Foster Care Histories. Child Maltreatment, 27(4), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211034763

[6]Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2022). Extension of foster care beyond age 18. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/laws-policies/statutes/extensionfc/

[7]Avant, D. W., Miller-Ott, A. E., & Houston, D. M. (2021). “I Needed to Aim Higher:” Former Foster Youths’ Pathways to College Success. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30, 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01892-1

Categories

Child Development & Well-Being, Child Maltreatment & Child Welfare System, Children, Economic Support, Economic Support General, Education & Training, Employment, Employment General, Job Training, K-12 Education, Postsecondary Education, Transition to Adulthood