- March 2020

- Fast Focus Research/Policy Brief No. 46-2020

Research across a range of disciplines suggests that involved fathers can have unique positive influence on their children’s social, emotional, and cognitive outcomes. Studies also find that mothers and fathers themselves also benefit when fathers are involved in child-rearing.[1] Involved fathering is sensitive, warm, close, friendly, supportive, affectionate, nurturing, encouraging, comforting, and accepting.[2]

Numerous rigorous studies also point to negative effects of father absence, including lower children’s educational attainment, especially high school graduation; less social-emotional adjustment; and more mental health issues in adulthood than seen in people who had an involved father.[3]

Despite this growing recognition of fathers’ potential importance to children and families, most family services programming, such as home visiting, was designed with only mothers in mind. Although this is changing, and programs increasingly seek to include fathers, many programs still have not examined involved fathers’ unique role in raising well-adjusted children.[4]

Today’s dads are a diverse group.

Fathers (and families) today are a diverse group; men raising children can be biological, social, legal, and stepfathers, as well as grandfathers, uncles, or big brothers.[5] Dads’ circumstances also vary, with some serving in the military and others being incarcerated, either of which can complicate their involvement with their children. This diversity in fatherhood roles and circumstances suggests the need for careful design of interventions to remove barriers to their involvement and engage them in programming.

Many service providers are working to improve their father-friendliness.

Experts recommend that programs seeking to improve their reach and effectiveness in working with fathers first make an effort to understand the unique barriers to family services involvement they face (see common barriers below). Programs can then use the “What works” list (see text box) to do a program self-assessment and implement new strategies as needed.

Practitioners who have successfully engaged dads in programming say planning is key, such as knowing fathers’ schedules and what they like to do with their kids. They also recommend having dads run activities, and implementing programming that is responsive to dads’ needs and interests. For example, a rural provider had a community “Bring in Your Truck Day” for dads that was also open to grandfathers, uncles, and brothers to show and tell their vehicle.[6] Children reported that the event was very exciting and they were proud of their fathers. Another event had a barber teach fathers how to cut their children’s hair.

- Communicate directly with fathers, including nonresident dads, and extend a personal invitation to participate;

- Adjust program schedule to meet fathers’ needs;

- Create a father-friendly environment;

- Give warm welcomes, greeting participants by name;

- Offer materials created for fathers;

- Presume fathers’ high interest;

- Recognize and reinforce their contributions;

- Learn what fathers want and offer it;

- Find out about and respond to fathers’ individual circumstances;

- Offer resources to achieve parenting and related goals;

- Collaborate with other providers; and

- Look for and take advantage of moments of opportunity when fathers are especially motivated (e.g., baby’s birth).*

Home visiting programs are engaging dads by paying attention to their needs.

More systemic changes may also yield positive outcomes. For example, some home visiting programs that typically target pregnant women and mothers of young children in at-risk families are now engaging fathers as well as mothers. Promising practices include providing home visitors with father-specific information and having separate visits for mothers and fathers, with male home visitors serving as mentors.[7]

Barriers to father involvement in family services can be provider-based, practical, or motivational.

Provider-based barriers: Failure to include fathers explicitly in invitations; personal biases, such as dismissal of fathers’ participation as important; personal discomfort with conflict between parents; and confusion about when and how to involve fathers.

Fathers’ practical barriers: Conflicting work schedule; military deployment; incarceration; instability (e.g., homelessness, substance use); and competing responsibilities.

Fathers’ motivational barriers: Reticence due to lack of other fathers participating; lack of male program staff; tension with child’s mother; and lack of clarity about benefits of participation.[8]

Fathers who are absent due to military deployment and those returning home postdeployment need supports.

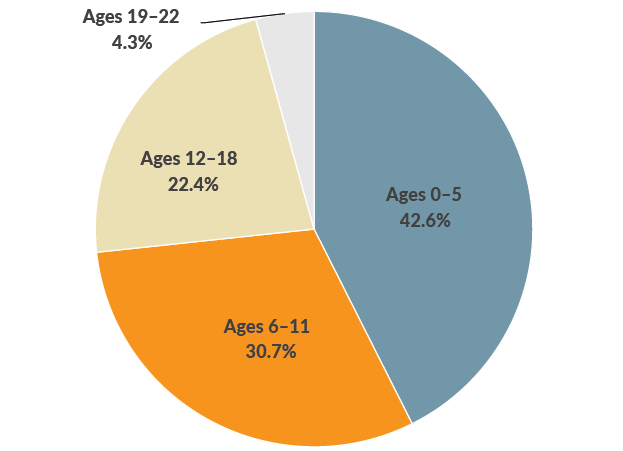

Source: U.S. Department of Defense, 2018 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community, 2019.

Notes: This pie graph depicts the percentage of dependent children of Active Duty military members by child’s age. Children ages 21 to 22 must be enrolled as full-time students in order to qualify as dependents. Percentages may not total to 100 due to rounding.

Since 2001, some 2.7 million American troops have been deployed to the Middle East, 44 percent of whom are parents (mostly fathers). Of the 1.65 million children with a parent serving in the military, 38 percent are under 6 years old (see Figure 1).[9] A qualitative study of military fathers revealed the dads were very invested in their relationship with their child but that they lacked confidence in their parenting skills.

This hesitance can be intensified when children’s needs change while dads are on deployment. When they return, dads find that their children kept growing and developing in their absence, and their new stage of development calls for a different parenting approach. Providers can help ease this return to parenting by offering dads education about early childhood development, age-typical behaviors, and developmentally appropriate discipline.[10]

Returning home after deployment also can present other challenges. For example, when their child expresses negative emotions some fathers say they feel triggered and remember stressful military experiences. Many dads have profound experiences of loss during their deployment that make it hard to reconnect emotionally with their children and partner postdeployment.[11] Providers who are aware of these challenges can help families ease the transition when fathers return.

Supports in prisons and schools can help to address the challenges faced by incarcerated dads and their children.

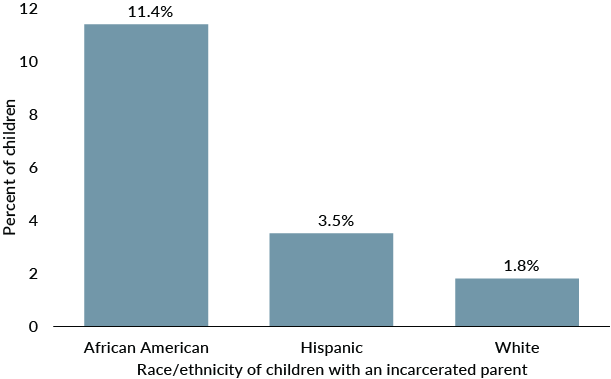

Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts: Pew Center on the States, “Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility,” Washington, D.C., 2010.

The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that at the end of 2017, almost 1.5 million people were imprisoned, the majority of whom were African American males under age 40.[12] In 2017, for every 100,000 adult U.S. residents, 272 whites and 1,549 blacks were imprisoned. Almost seven times as many black children than white children have an incarcerated parent, and the disparity between black and Hispanic children also is big (Figure 2). About half of the children with an incarcerated parent are under 10 years old.[13]

Incarcerated dads and their children need extra supports. For example, prisons can support positive visitation experiences for dads and their kids by adjusting their standard practices (see below).[14] Schools can support children with incarcerated parents by providing specialized training to teachers and counselors.[15] A web resource created by several U.S. government agencies—youth.gov—includes a tip sheet for preschool through grade 12 teachers on how to support children who have an incarcerated parent.[16] Tips include

- understanding that having an incarcerated parent is a traumatic experience;

- being sensitive to “trigger” topics in the classroom such as current events involving crime or arrests;

- working with the child’s other parent or caregiver to create a positive school setting; and

- having teachers establish themselves as a trusted and caring adult who challenges the stigma and shame that can be associated with having a parent in prison.

The push for sentencing reform—half of the people in federal prisons are serving time for a drug offense, for which treatment might be a more effective approach[17]—could reduce incarceration’s harm to families. Two reform strategies under discussion are to shorten mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenses and use parole rather than imprisonment as a sanction.[18]

- Space to create a child-friendly contact visiting room and/or family-friendly noncontact visiting area;

- Visiting booths (e.g., space to paint a mural, add posters, and/or furniture);

- Buy-in from the administration to integrate child- and family-friendly visiting policies and practices (e.g., parent/child contact visiting, use of child-sensitive visitor-search practices, pre- and post-visiting support for both children and parents);

- Supplies for family visits such as age-appropriate books, games, toys, puzzles, play mats;

- Partnerships with community-based or nonprofit organizations to facilitate visits; and

- Correctional staff trained on how to interact with children and families during visits.

Policy/Practice

Policymakers, pediatricians, child support agencies, and family-services practitioners are making efforts to be father-friendly with the understanding that the more each individual family member’s needs are met, the stronger the family as a whole will be (see Table 1).[19]

| Table 1. How policymakers and service providers can support and encourage positive father involvement. | |

| Policymakers |

Provide paid paternal leave to allow fathers to stay home and bond with their infants and care for sick children.

Fund public-service announcements promoting positive, involved fathers and modeling effective coparenting relationships.

|

| Pediatricians | Involve fathers in health care discussions during appointments. |

| Social service providers |

Improve “father-friendliness” of programs and help fathers take stock of what they are doing for their children and where they could do more.

Encourage positive coparenting to help facilitate nonresident father involvement with their children.

|

| Child support caseworkers | Inquire about noncustodial fathers’ barriers to spending time with their children and offer to help facilitate visits. |

| Home-visiting providers | Engage fathers in programming, either in concert with or separate from maternal home visits. |

| Source: Rows 1–3: Tova Walsh, “Strategies for Involving and Engaging Fathers in Programming,” IRP webinar; Row 4: Maria Cancian, Daniel R. Meyer, and Robert Wood, “Final Impact Findings from the Noncustodial Parent Employment Demonstration”; Row 5: Sandstrom et al., Approaches to Father Engagement and Fathers’ Experiences in Home Visiting Programs. | |

Notes

[1]Special thanks to Tova Walsh, Assistant Professor of Social Work, University of Wisconsin–Madison, whose Institute for Research on Poverty webinar with L. Zach, P. Fendt, and D. Davidson, “Strategies for Involving and Engaging Fathers in Programming,” March 27, 2019, provided the basis for this brief. For a summary of the literature on fathers’ contributions to children, mothers, and families, see Involved Fathers Play an Important Role in Children’s Lives, Fast Focus No. 45, Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison; see also, J. R. Snarey, How Fathers Care for the Next Generation: A Four-Decade Study, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 1993.

[2]S. Allen, K. Daly, “Influences of Father Involvement on Child Development Outcomes,” The Father Involvement Initiative ONews, 1, fall 2002.

[3]S. McLanahan, L. Tach, and D. Schneider, “The Causal Effects of Father Absence,” Annual Review of Sociology 39 (2013): 399–427.

[4]N. B. Guterman, J. L. Bellamy, and A. Banman, “Promoting Father Involvement in Early Home Visiting Services for Vulnerable Families: Findings from a Pilot Study of “Dads Matter,” Child Abuse & Neglect 76 (February 2018): 261–272.

[5]Definitions of terms: A social father is a man who is married to or cohabiting with a child’s mother but is not the child’s biological father; a legal father is a man recognized by law as the male parent of a child; a stepfather is the husband of one’s parent when different from a child’s biological or legal father; in a recombined family, one or both of the spouses have been divorced or widowed and have remarried and formed a new family that includes children from one or both first marriages and/or from the remarriage.

[6]B. Peterson, J. Fontaine, L. Cramer, A. Reisman, H. Cuthrell, M. Goff, E. McCoy, and T. Reginal, “Model Practices for Parents in Prisons and Jails: Reducing Barriers for Family Connections,” Urban Institute, July 2019.

[7]T. Walsh, L. Zach, P. Fendt, and “Strategies for Involving and Engaging Fathers in Programming,” webinar, Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin–Madison, March 27, 2019.

[8]Walsh, Zach, Fendt, and Davidson, “Strategies for Involving and Engaging Fathers in Programming.”

[9]U.S. Department of Defense, Demographics Report: Profile of the Military Community, 2018.

[10]T. B. Walsh, C. J. Dayton, M. S. Erwin, A. Busuito, M. Muzik, & K. L. Rosenblum, “Fathering after Military Deployment: Parenting Challenges and Goals of Fathers of Young Children, Health and Social Work 39 (1, 2014): 35–44.

[11]T. Walsh, “Fathering after Military Deployment,” Institute for Research on Poverty podcast, May 2014.

[12]J. Bronson and E. A. Carson, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2017, summary, NCJ252156, April 2019.

[13]The Pew Charitable Trusts: Pew Center on the States, “Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility,” Washington, D.C., 2010.

[14]See also, J. M. Eddy, and J. Poehlmann-Tynan, (Eds.), Handbook on Children of Incarcerated Parents, 2nd edition, New York: Springer, 2019; and Poehlmann-Tynan’s website.

[15]E. C. Brown and C. A. Barrio Minton, “Serving Children of Incarcerated Parents: A Case Study of School Counselors’ Experiences,” Professional School Counseling, June 6, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2156759X18778811.

[16]Tip Sheet for Teachers (Pre-K through 12): Supporting Children Who Have an Incarcerated Parent,” https://youth.gov/youth-topics/children-of-incarcerated-parents/federal-tools-resources/tip-sheet-teachers.

[17]See Program Profile: Drug Treatment Alternative to Prison (DTAP), Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, May 25, 2011; see also, the Sentencing Project, Sentencing Policy.

[18]M. Mauer, “The Impact of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in Federal Sentencing,” The Sentencing Project, September 22, 2010; and Alternatives to Incarceration, Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. See also, N. Damron, “Life Beyond Bars: Children with an Incarcerated Parent,” Poverty Fact Sheet.

Categories

Family & Partnering, Family Structure, Parenting