- October 2021

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 55-2021

Even though there has been a slight decrease in the United States incarceration rate since its peak in 2009, the U.S. still incarcerates a larger percentage of its population than any other country for which data is available.[1] The situation is especially serious for Black and Native American individuals; for example, Black people are incarcerated at much higher rates than their Hispanic and White counterparts—twice as much and five times as much, respectively.[2] In addition, more than half of the young, low-income men of color who are overrepresented in jail populations are fathers.[3]

An estimated 5 to 8 million children have had a parent incarcerated in jail or prison, a figure representing about 7% of U.S. children. And those rates have risen 79% in the last three decades.[4] Having an incarcerated parent can impact children in many ways, including increased risk of living in poverty, housing instability, household stress, involvement in other systems, and a reduction or strain to the child’s relationship with the incarcerated parent.

When A Child Is Present When A Parent Is Arrested

Within this group is the subgroup of children who are physically present when a parent is arrested. Each situation is unique, but many involve a forcible entry into the residence, violence in the process of restraining the parent and their removal in handcuffs, and transport in a police vehicle away from the child and the home. The experience of witnessing the arrest can be traumatic for any child, but younger children are particularly vulnerable. Again, people of color are at greater risk of arrest when detained by law enforcement; not only are Black adults arrested at much higher rates than their White counterparts, but arrests of Black and Hispanic adults are 50% more likely to involve the use of force,[5] which adds to the trauma of child witnesses. There are not clear data on how many children see a parent arrested, but some research estimates that between 22 and 41% of children who either were the subject of a CPS case or had an incarcerated parent were present for a parental arrest.[6]

Physical and Behavioral Effects Of Witnessing Parental Arrest

The physical and developmental consequences for children who witness parental arrest are becoming more clear through recent research, and the results are concerning. A recent paper by researchers Luke Muentner, Amita Kapoor, Lindsay Weymouth, and Julie Poehlmann-Tynan details the links between stress hormone production and behavioral responses when a child is present for the arrest of a parent.[7] Their goal is to measure how that experience alters children’s physiological stress response and what impact that can have on both short- and long-term health and development.

Chronic stress and the resulting production and levels of stress hormones during childhood can affect mental and physical health, including brain development. To assess the consequences for children who witnessed their father’s arrest, the researchers received parental and child consent to collect hair samples from the child to measure the stress hormones cortisol and cortisone. This is a reliable method for measuring stress responses over time instead of a snapshot that is indicative of other collection methods. In this particular study, the hair samples were taken approximately 60 days after the father’s arrest, providing nearly two months of data to assess.

The research team focused on incidents leading to incarceration in three jails, all in jurisdictions that did not have set protocols for how to proceed with children present at the time of arrest. They also accounted for other layers of stress and trauma—like seeing a crime being committed or witnessing domestic violence—in their analyses. In addition to hair samples, they collected observations about distress levels related to the arrest and separation, as well as behavioral changes as reported by the children’s caregivers.

The severity of children’s distress was rated on a scale of one to five, with 5 being the highest. The mean was 4.09 for children who observed the arrest, compared to a mean of 2.75 for those who witnessed a crime instead. Caregivers’ reports of children’s behavioral stress were collected using a validated checklist that accounted for their subsequent lowered ability to concentrate, exhibiting nervousness, stubbornness, mood changes or sadness, and physical manifestations like nausea and stomach aches.

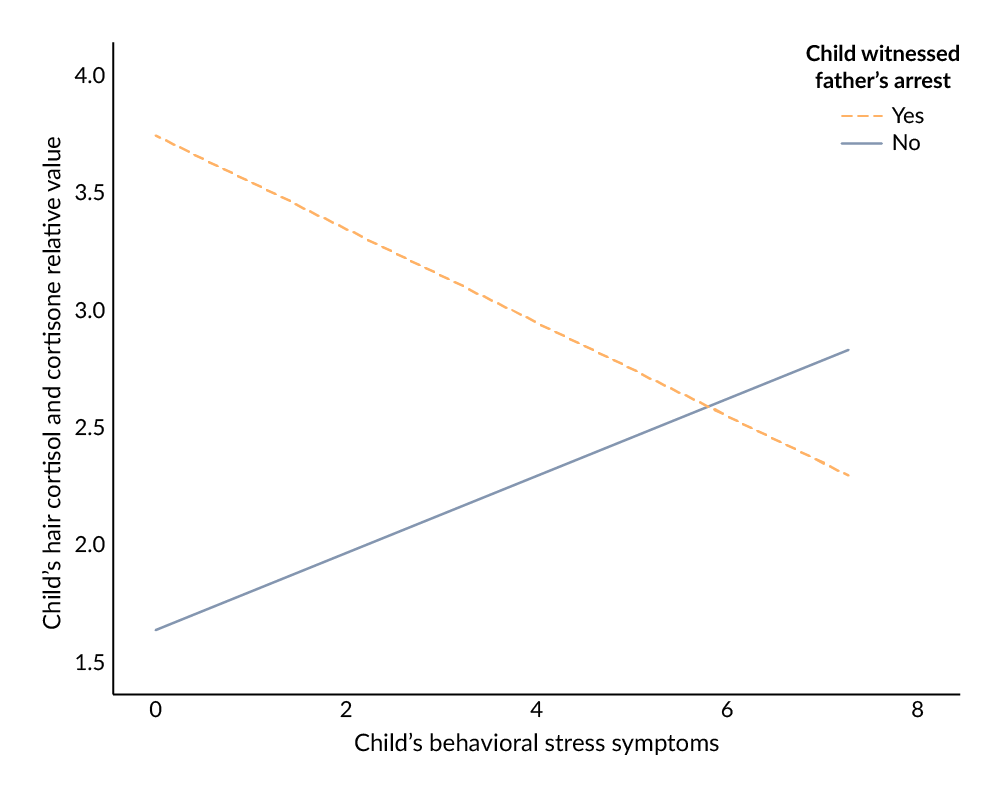

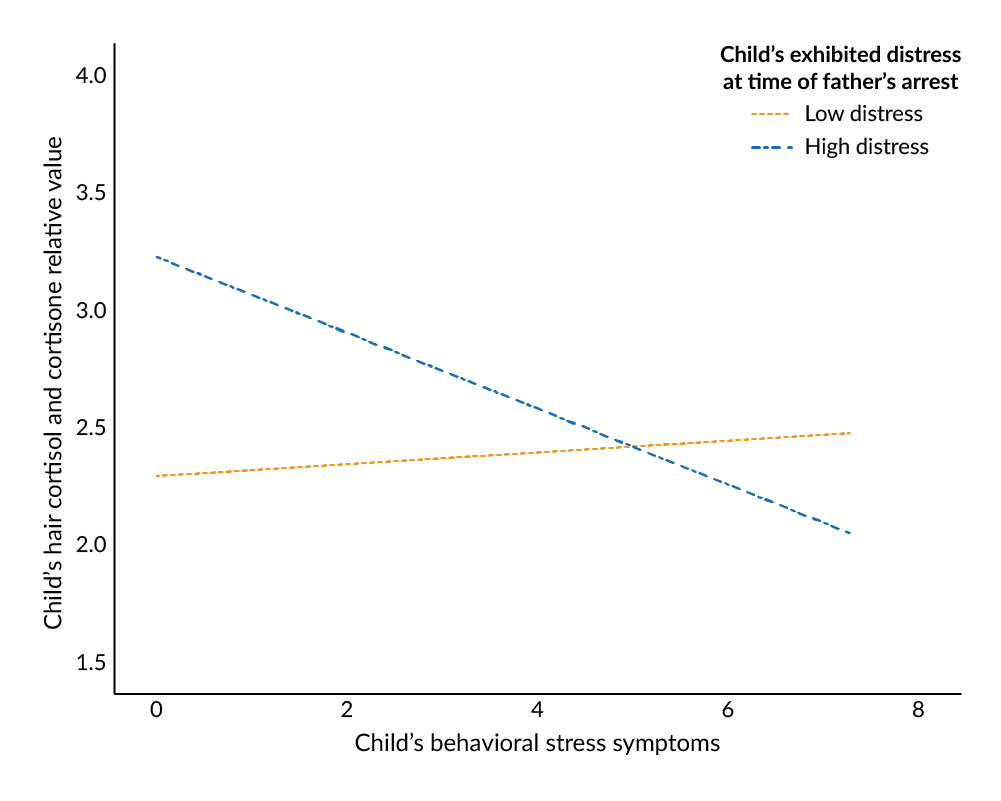

The findings show that children who witnessed their father’s arrest had elevated cumulative levels of stress hormones in their hair samples overall compared to those who did not witness an arrest. However, their level of behavioral stress may influence the ways in which this exposure gets “under their skin” (Figure 1). For instance, when children exhibited low or moderate behavioral stress symptoms, the cortisol and cortisone concentrations in their hair sample spiked and were higher—perhaps indicative of the body’s normative “fight or flight” response to stressful situations. On the other hand, the children who were already experiencing significantly high behavioral stress symptoms saw their stress response systems effectively shut down as evidenced by lower concentrations of cortisol in their samples (Figure 2). The lower concentrations in this second instance may seem counter-intuitive, but in fact, it mirrors the blunting effect that can be present in individuals who are suffering with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or chronic stress.

Source: Adapted from Figure 2, Muentner, L., Kapoor, A., Weymouth, L., & Poehlmann‐Tynan, J. (2021). Getting under the skin: Physiological stress and witnessing paternal arrest in young children with incarcerated fathers. Developmental Psychobiology.

Source: Adapted from Figure 2, Muentner, L., Kapoor, A., Weymouth, L., & Poehlmann‐Tynan, J. (2021). Getting under the skin: Physiological stress and witnessing paternal arrest in young children with incarcerated fathers. Developmental Psychobiology.

The mechanisms regulating stress hormones are complex. The release of cortisol and cortisone by the adrenal glands at the time of a stressful event—in this case, when a child sees their father arrested—happens consistently. In a normal stress response, parts of the brain that are responsible for higher functions kick in to reduce the levels of stress hormones and moderate their impact. For some people, this may be when they go into a “fight or flight” mode—their heart may race, palms may get sweaty, and they may act with a sort of hypervigilance. But for individuals who suffer from chronic stress, like the children with high behavioral stress symptoms in this study, those systems are rendered less sensitive and as a result, less effective. This means that the physiological consequences of witnessing a parent’s arrest may be most detrimental to children who are already stretched thin and chronically stressed in other areas of life.

The Impact Of Chronic Stress On Children

Chronic stress has been linked to health outcomes that include anxiety, depression, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. It is known to adversely affect brain development and health in several regions responsible for different functions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, and pre-frontal cortex. Evidence suggests that these effects can be reversed if the chronic stress is relatively short-lived, but the longer-term effects of ongoing stress are unknown, particularly whether the effects of chronic stress at some point becomes irreversible. These effects may be especially detrimental for children’s developing brains.

It can be difficult to pinpoint a relationship between a child’s experience of chronic stress and their behavior because they may respond in different ways from their peers. Some children may “act out” in ways that include rage, antisocial behavior, social withdrawal, or feelings of helplessness. Other may instead “shut down” and not exhibit outward responses that can be gauged. There are also other factors that can increase the impact of chronic stress; for example, children of color may also be dealing with the effects of systemic racism and other oppressions that can produce physiological reactions as well. Thus, a major contribution of this study is moving the field beyond only parental reports of more overt forms of children’s adjustment to include more nuanced measures of how associated trauma spurred by involvement with the criminal justice system may get under children’s skin.

Implications And Policy Recommendations

A better understanding of how and why children respond as they do to both acute and chronic stress is crucial to promote policies that can mitigate the effects and to support children after experiencing stressful events and living conditions. This could lead to fewer children being subject to long-term stress and the negative mental and physical health impacts it can have on their well-being.

In the case of children witnessing the arrest of a parent, best practices for ensuring child safety during the event are available from the International Association of Chiefs of Police and should be customized and implemented in law enforcement agencies across the board.[8] These include having protocols and procedures that are triggered when a child is present and may include delaying the arrest until the child can be removed, modifying arrest methods and limiting violence, giving the child a comfort item like a piece of the parent’s clothing or a stuffed animal, and allowing the parent to talk with the child before they are taken away. Follow-up services to help children process the trauma in a supportive environment are also recommended. The more we learn how these experiences in effect get “under the skin” of children, the more prepared we will be as a society to reduce exposure and support healthy development.

[1]Gramlich, J. (2021, August 16). America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995. Pew Research Center.

[2]Gramlich, J. (2020, May 6). Black imprisonment rate in the U.S. has fallen by a third since 2006. Pew Research Center.

[3]Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2020). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2020. Prison Policy Initiative.

[4]Murphey, D., & Cooper, P. M. (2015). Parents Behind Bars: What happens to their children? Child Trends.

[5]Fryer Jr., R. G. (2019). An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. Journal of Political Economy, 127(3), 1210–1261.

[6]Dallaire, D. H., & Wilson, L. C. (2010). The relation of exposure to parental criminal activity, arrest, and sentencing to children’s maladjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 404–418.

[7]Muentner, L., Kapoor, A., Weymouth, L. and Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2021), Getting under the skin: Physiological stress and witnessing paternal arrest in young children with incarcerated fathers. Developmental Psychobiology, 63, 1568–1582.

[8]International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2014). Safeguarding Children of Arrested Parents.

Categories

Child Development & Well-Being, Children, Family & Partnering, Family Structure, Health, Health General, Justice System, Parenting, Policing