- August 2021

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 54-2021

A study by Leslie Hodges and Lisa Klein Vogel published in late 2020 looked at differences in how states set child support orders for low-income parents based on recently adopted federal guidelines.[1] These guidelines are the result of federal legislation that requires states to consider noncustodial parents’ ability to pay when setting child support orders. The legislation, however, leaves it up to states to decide how to balance the financial constraints of parents paying child support with the economic needs of their children.

Child support payments can be a buffer against child poverty, but noncustodial parents’ ability to pay can be a significant barrier

It is common for children in the United States to live in single-parent households, which is a risk factor for child poverty.[2] Child support paid by the noncustodial parent is often an important source of income for the custodial parent’s household and can be a buffer against poverty.[3] Yet nonpayment of child support is a significant problem. In 2017, over half of custodial parents with child support orders did not receive the amount due to them and 30% did not receive any support at all.[4]

For noncustodial parents with limited economic resources, inability to pay is major reason for nonpayment of support.[5] Nearly all states now incorporate special considerations for low-income noncustodial parents in their child support guidelines but balancing the financial needs of the paying parent with their child’s support needs remains a complex issue.

The Office of Child Support Enforcement directed states to consider noncustodial parents’ ability to pay when setting order levels

In December of 2016, the Office of Child Support Enforcement (OCSE) issued the Flexibility, Efficiency, and Modernization in Child Support Enforcement Programs Final Rule, which directed states to set orders that considered the noncustodial parent’s subsistence needs and ability to pay support. This represents a shift because traditionally, parental responsibility and the needs of the child have been seen as the most important concerns in the setting of orders. The developers of the new rule expected that it would lead to orders that low-income noncustodial parents were better able to pay, and that the consistency of child support payments would increase.

Hodges and Vogel examined child support guidelines for the states that had released information about reviews done between 2017 and 2020. The authors also calculated order amounts for several types of low-income child support cases for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Hodges and Vogel found that for lower-income payers, states fell on a spectrum in how they balanced parental financial responsibility for their children and parental self-sufficiency when setting orders. Some states prioritized the parent’s ability to meet their own basic needs, while others put the support needs of the child first. Many states fell somewhere in the middle.

There is significant variation in what states consider the right amount of child support

When Hodges and Vogel calculated monthly order amounts based on each state’s child support guidelines, they created four different scenarios that varied the noncustodial parent’s income given a set level of income for the custodial parent. For this study, they designated the mother as the primary custodial parent with the children staying every other weekend with the father, the noncustodial parent. The fathers’ income scenarios were set at the following levels:

- State median earnings

- Half of the state median earnings

- Full-time at state minimum wage

- Part-time at state minimum wage

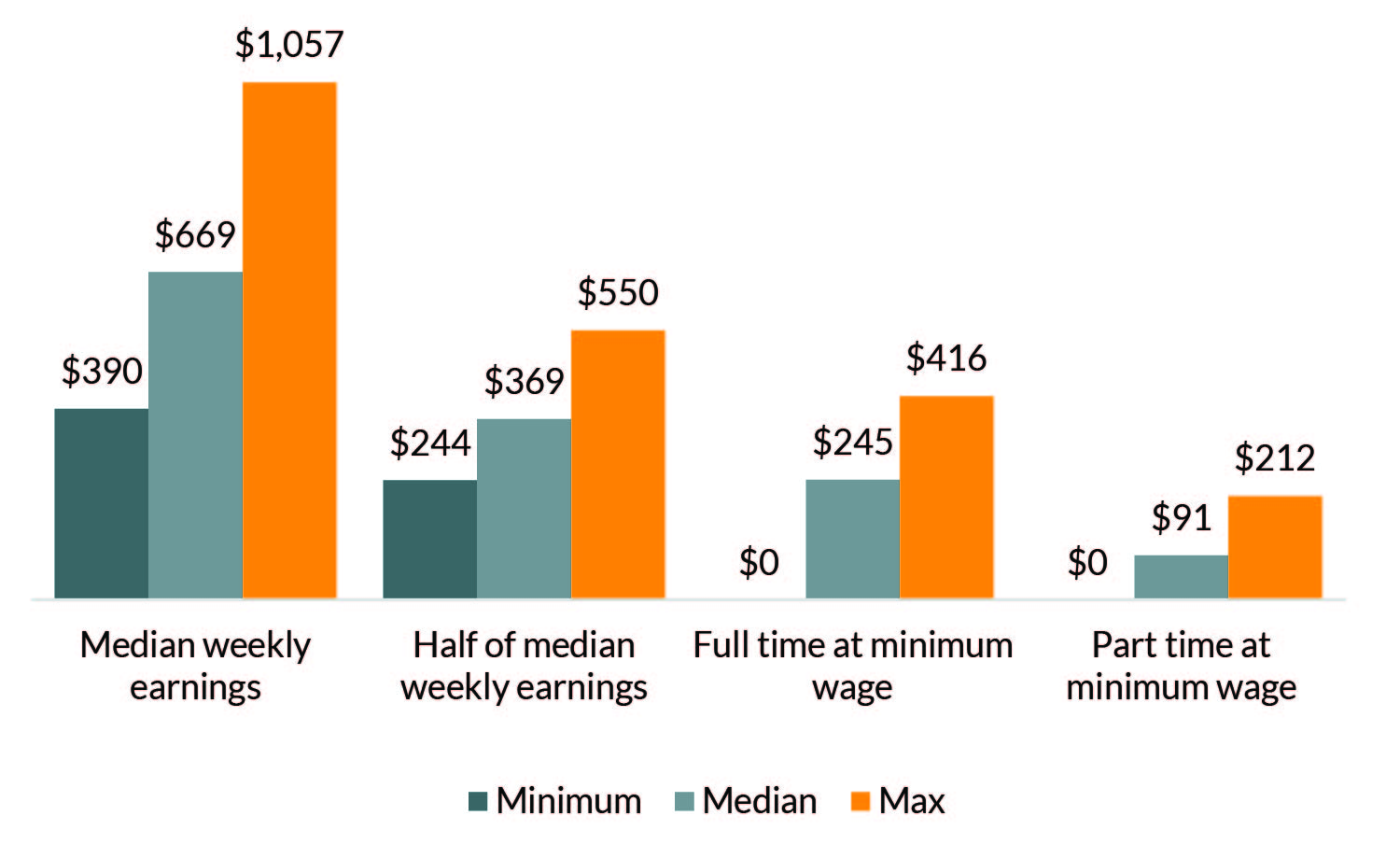

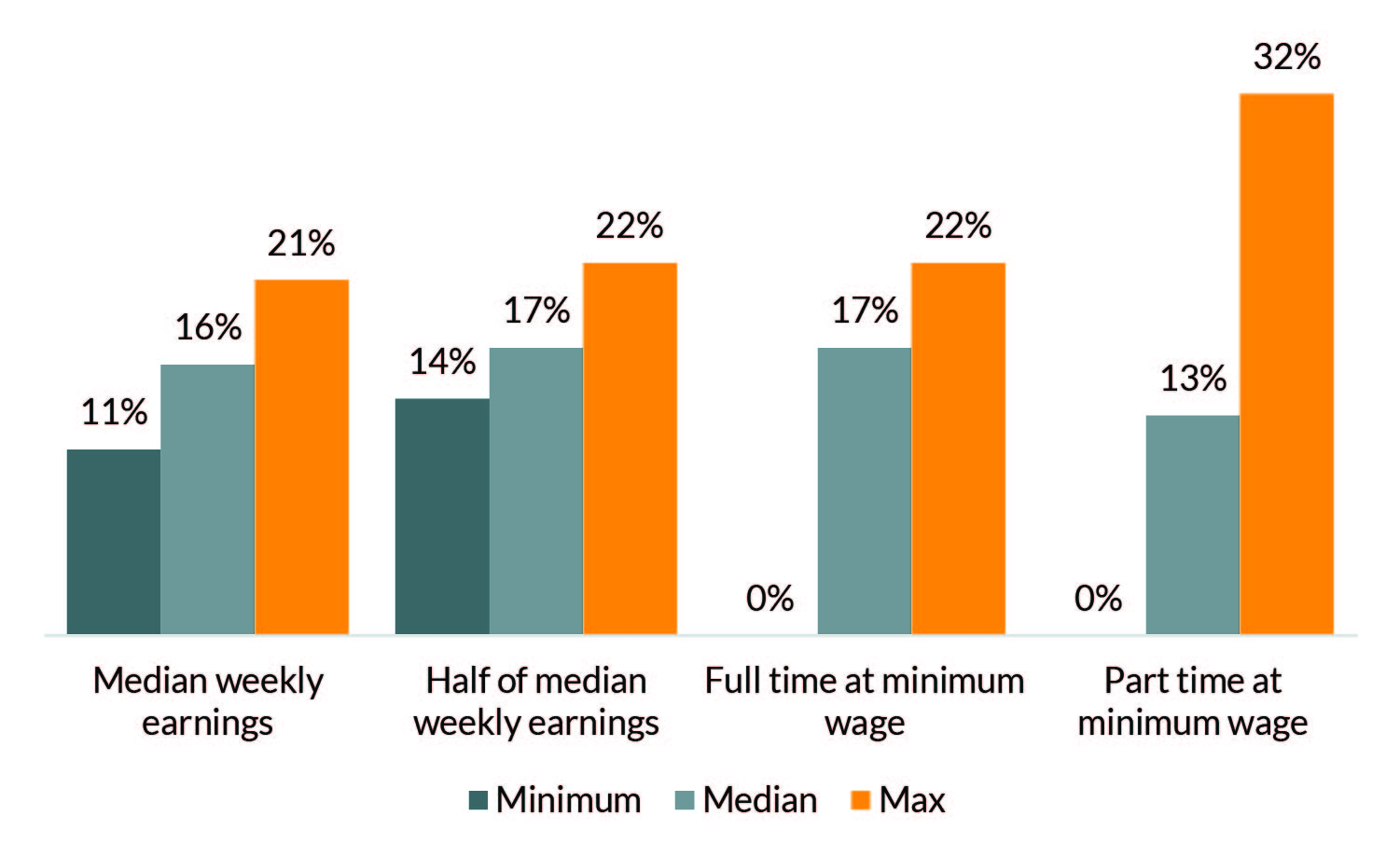

There was large variation in the monthly orders from state to state. Figure 1 shows the low, the median, and the high dollar amount of monthly orders under each scenario. However, because there are notable differences in both the median wages and minimum wages by state, it is useful to look at child support orders as a percentage of the payers’ monthly income, as in Figure 2.[6]

Hodges and Vogel’s analysis reveals some notable patterns. As might be expected, order amounts for median earning fathers were about twice those of the half-median earning fathers. However, there was more variation for lower-income fathers. For both the full-time and part-time minimum wage groups, minimum order amounts were as low as $0 in some states, but the median order amount was almost three times higher for the full-time minimum wage scenario than for the part-time scenario.

In some states, the lowest-earning fathers paid a disproportionate amount of their income relative to higher-earning fathers (see Figure 2). There was also more variation in the burden levels for fathers at part-time minimum wage compared to those with full-time minimum wage earnings, and the part-time minimum wage fathers actually had higher burden levels in some states. This could be because of factors like set minimums on order amounts or because some states assigned full-time minimum wage income levels to fathers even if their actual earnings were lower.

Source: Hodges, L., & Vogel, L. K. (2020). Too much, too little, or just right? Recent changes to state child support guidelines for low-income noncustodial parents. Journal of Policy Practice and Research.

Note: These amounts shown in Figures 1 and 2 are based on Hodges and Vogel’s calculations for orders with one child. The mothers’ monthly earnings are set at the level of the median area earnings for women.

Source: Hodges, L., & Vogel, L. K. (2020).

Self-Support Reserves (SSRs) and other low-income deviations reduce burdens for the lowest earning fathers, but had relatively little impact on the support burdens of other earnings groups

The study also looked at whether state guidelines adjusted for the situations of lower-income noncustodial parents. The authors examined the median order amounts for states in three categories: (1) those with Self-Support Reserves,[7] the amount necessary to provide for one person’s basic needs calculated at a percentage of the federal poverty line; (2) those with other types of deviations for low income, such as alternative calculations for low-income noncustodial parents; and (3) those that did not make any adjustments. These factors and guidelines impact the amount owed through a child support order. A few factors stood out:

- States that did not adjust for low incomes had smaller order amounts for fathers in the median income and half-median income scenarios than those that did.

- For states with SSRs, order amounts were actually higher for the full-time minimum wage scenario fathers than in states without them. Order amounts in states with other low-income deviations were similar to those in states with no deviations.

- For the lowest-income father scenario, states’ use of SSRs or other low-income deviations led to reductions in the median support orders.

Differences between the full- and part-time minimum wage scenarios are likely due to variations in the levels at which SSRs or other deviations are applied. For example, many states use 100% of the federal poverty level as the threshold for setting an SSR. In most cases, fathers at part-time minimum wage levels would fall under this threshold while those at full-time levels would not.

Conclusion: Balancing the needs of the paying parent with those of the child is important, especially in light of the pandemic-induced economic downturn

The precariousness of low-wage work, especially since early 2020, underscores the importance of finding a good balance between the financial needs of child support-paying low-income parents and the support needs of their children. When child support payments are not guaranteed by the government, it is critical that guidelines be written in a way that allows paying parents to be self-sufficient while also ensuring that children receive the support they need. Hodges and Vogel’s findings suggest that if a state wants to maximize noncustodial parent self-sufficiency, generous SSRs and no minimum order amounts can be an important step. Meanwhile, more gradual adjustments in orders for low-income parents may better maximize financial contributions to children.

[1]Hodges, L., & Vogel, L. K. (2020). Too much, too little, or just right? Recent changes to state child support guidelines for low-income noncustodial parents. Journal of Policy Practice and Research.

[2]U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Table FM-1. Families by presence of own children under 18: 1950 to present. Current Population Survey, March and Annual Social Economic Supplements, 2019 and earlier. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. National Academies Press.

[3]Ha, Y., Cancian, M., & Meyer, D. R. (2018). Child support and income inequality. Poverty & Public Policy, 10(2), 147–158.

[4]Grall, T. (2020). Custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2017, Current population reports, P60-269. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce, Economic and Statistics Administration.

[5]Vogel, L. K. (2020a). Barriers to meeting formal child support obligations: Noncustodial father perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104764; Vogel, L. K. (2020b). Help me help you: Identifying and addressing barriers to child support compliance. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104763. Bartfeld, J., & Meyer, D. R. (2003). Child support compliance among discretionary and nondiscretionary obligors. Social Service Review, 77(3), 347–372.

[6]Both figures show order amounts for one child with the assumption that the noncustodial parent does not have other children in a different household.

[7]A self-support reserve (SSR) is a strategy used to address noncustodial parents’ limited financial resources. An SSR allows the parent to keep income up to a certain amount before an obligation is set.

Categories

Child Support, Child Support Policy Research, Guidelines, Orders & Payments

Tags

Custodial Parents, Fathers, Mothers, National, Noncustodial Parents/NCP