- May 2020

- Fast Focus Research/Policy Brief No. 48-2020

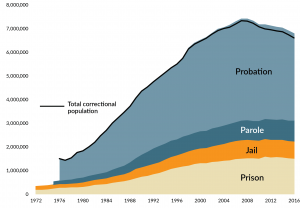

More than 6.5 million people in the United States—about equal to the population of Massachusetts—were either incarcerated, on probation, or on parole in 2016 (Figure 1).[1] Although this number has been declining since 2009, currently about one in every 100 adults are behind bars.

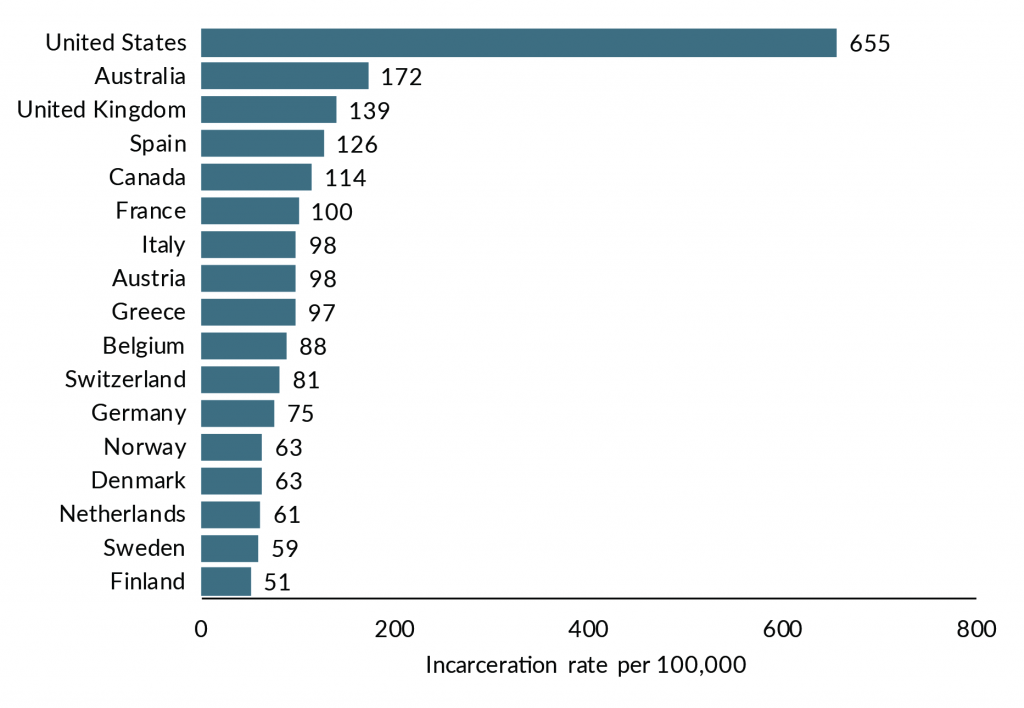

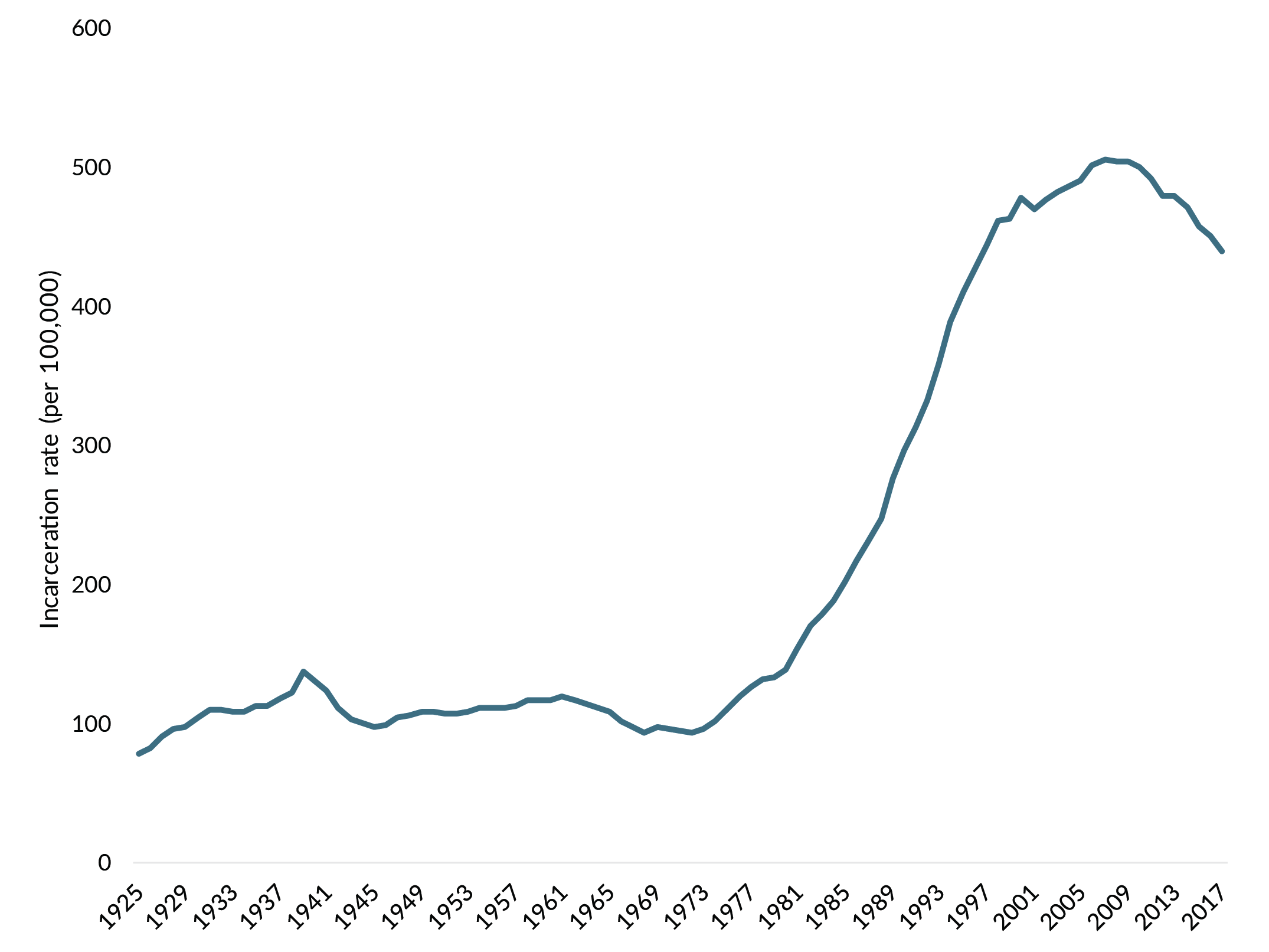

The United States has the highest incarceration rate, not only of any Western democracy (Figure 2), but also in the world. It wasn’t always this way. From the 1920s until the early 1970s, the U.S. rate of incarceration was stable and in line with other countries. However, between 1973 and 2009, the rate more than quadrupled (Figure 3).

Understanding what drove the dramatic increase is complicated. The rise in imprisonment happened when crime was actually historically low, including the lowest homicide rate since the early 1960s, so greater criminal activity is not a plausible explanation.[2]

Some studies suggest that policy changes—such as imprisoning people for a wider range of offenses and imposing longer sentences—as opposed to increases in crime contributed to the sharp increase in incarceration.[3]

This brief explores the differences in incarceration by race, reviews related outcomes for individuals and families, and explores the challenges faced by those re-entering society after incarceration.

Note: Figure shows total correction population, including state and federal prison, local jail, and probation and parole populations, from 1972 to 2016. Individuals can have more than one correctional status, so the total correctional population may be less than the sum of those in each status.

Source: 1972 to 1979 data were compiled from the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics for The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, National Research Council Committee on Law and Justice, National Academy of Sciences, April 2014. The 1980 to 2016 data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Annual Probation Survey, Annual Parole Survey, Annual Survey of Jails, Census of Jail Inmates, and National Prisoner Statistics Program.

Note: Figure shows total rates of imprisonment, including pre-trial detainees and those who have been convicted and sentenced.

Source: R. Walmsley, World Prison Population List: 12th ed., Institute for Criminal Policy Research, University of London, 2018. Rates reported for selected Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.

Note: Figure shows imprisonment rates for sentenced prisoners who have received a sentence of more than one year in state or federal prison.

Source: 1925 to 2012 data are from the Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, Table 6.28.2012; 2013 to 2017 data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners in 2017,” Tables 3 and 5.

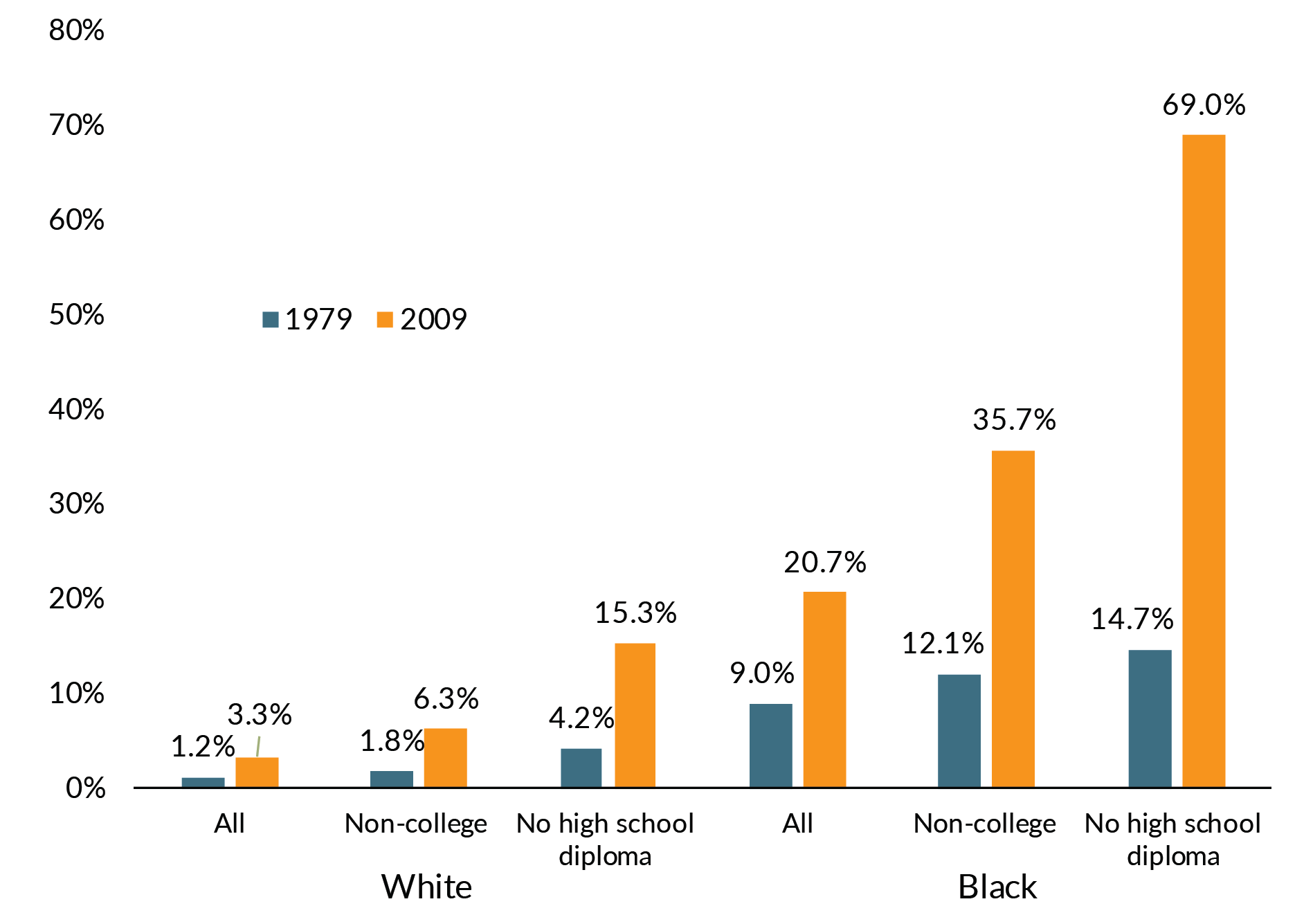

Inequality in incarceration by race, ethnicity, and education level is extensive.

The U.S. incarceration rate is not only high, but it’s also highly unequal. Prison populations disproportionately comprise African American and Hispanic men, especially men who dropped out of high school. Most of them are poor.[4]

Some researchers find links between high incarceration rates among men of color and policy changes that criminalized social problems experienced by many people living in poverty (who are disproportionately people of color). These challenges include homelessness, mental illness, and drug or alcohol problems. The result, these researchers suggest, perpetuates poverty and racial inequality both within and across generations.[5]

Figure 4 compares the risk of incarceration for black and white men in 1979 and 2009 by education level. While the risk increased for all groups between 1979 and 2009, the rise is particularly stark for black men who dropped out of high school. Almost 70% of the black high school dropouts in 2009 had been imprisoned at some point by age 30, which was four-and-a-half times the rate of white high school dropouts.[6]

Note: Figure shows the cumulative probability of male incarceration by age 30 to 34.

Source: B. Pettit, B. Sykes, and B. Western, “Technical Report on Revised Population Estimates and NLSY79 Analysis Tables for the Pew Public Safety and Mobility Project” (Harvard University, 2009).

It follows that just as unequal shares of black vs. white men are imprisoned, an unequal share of black vs. white children have a parent behind bars. About 1 in every 9 black children vs. 1 in every 57 white children have an incarcerated parent. Hispanic children are also more likely to have a parent in jail or prison (1 in 28) than white children.[7]

Incarceration is associated with poorer outcomes for children and families.

High levels of incarceration are associated with many negative consequences for individuals, families, communities, and society.[8] Because people of color are overrepresented in the prison population, families and communities of color have been disproportionately affected by the rise in incarceration.

Families of incarcerated men often experience economic hardship. Studies suggest that families with a father in prison are more prone to homelessness, difficulty meeting basic needs, and greater use of social assistance.[9] Financial adversity associated with incarceration can continue after the father’s release as ex-offenders struggle to get hired because of their prison record.[10]

Children with a father in prison are more likely to struggle with poor social, psychological, and academic outcomes than other children. These poor outcomes include depression, anxiety, and behavior problems such as aggression and delinquency.[11] These challenges are more common among boys and among children whose fathers were positively involved in their lives before going to prison.[12]

Less is known about whether maternal incarceration, which has grown rapidly in recent decades, affects their children. Studies to date have been based on small sample sizes. Therefore, more rigorous research is needed to draw strong conclusions about the possible negative effects of having a mother in prison.

Re-entering society after a prison sentence presents challenges.

The U.S. Department of Justice reports that over 10,000 ex-prisoners are released from state and federal prisons every week, and more than 650,000 are released every year. Studies estimate that approximately two-thirds of these former inmates will likely be rearrested within 3 years of release.[13]

Researchers are looking for what works to improve the transition back into society and prevent the return to prison. For example, the Boston Reentry Study, which examined life after incarceration from the perspective of people living it, provides insights into the challenges faced by those returning to society.

The Boston study researchers interviewed a group of formerly incarcerated people over their first year of reentering society.[14] The following major findings emerged from the interviews:

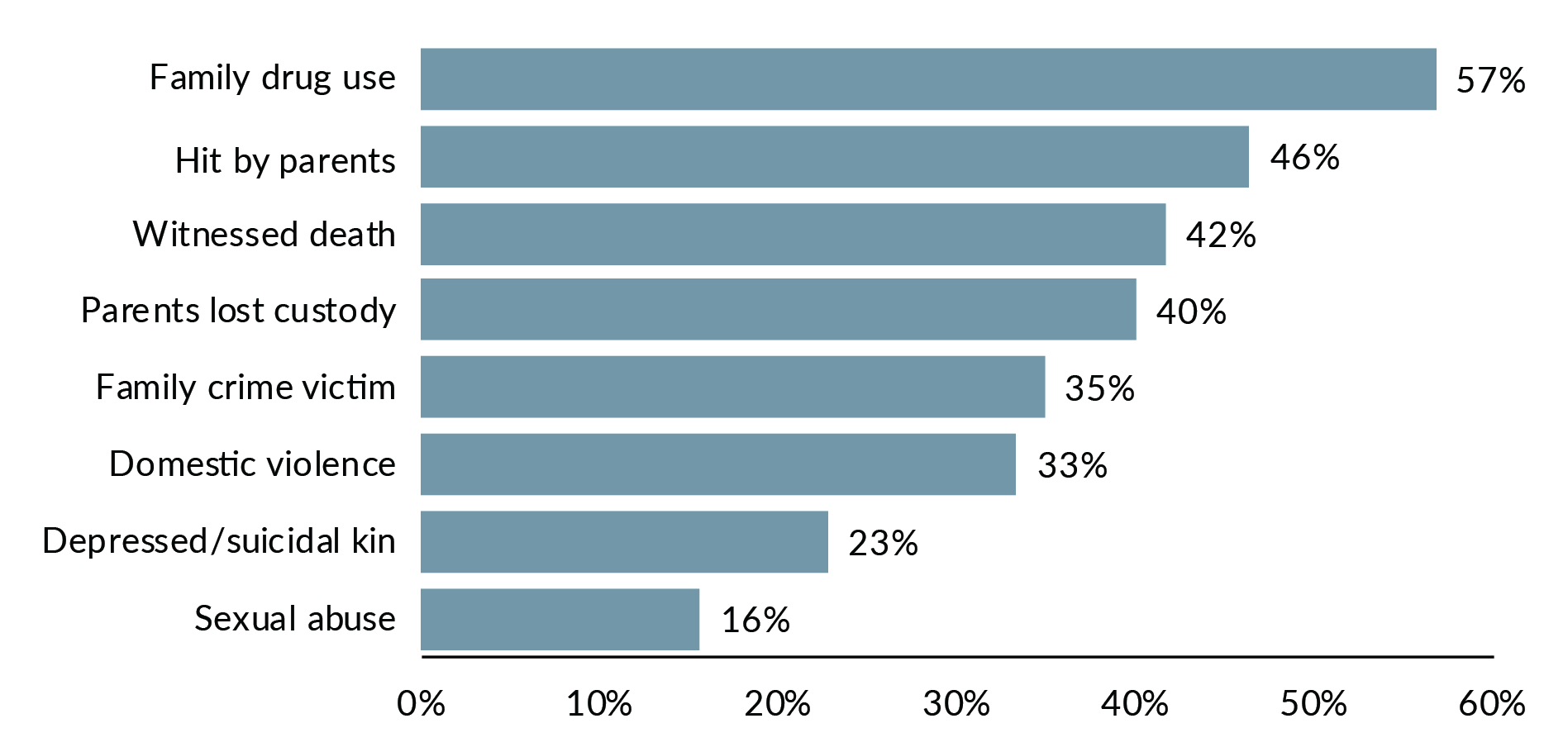

- Interviewers found many Boston Reentry Study participants revealed long histories of exposure to trauma in early childhood (Figure 5).

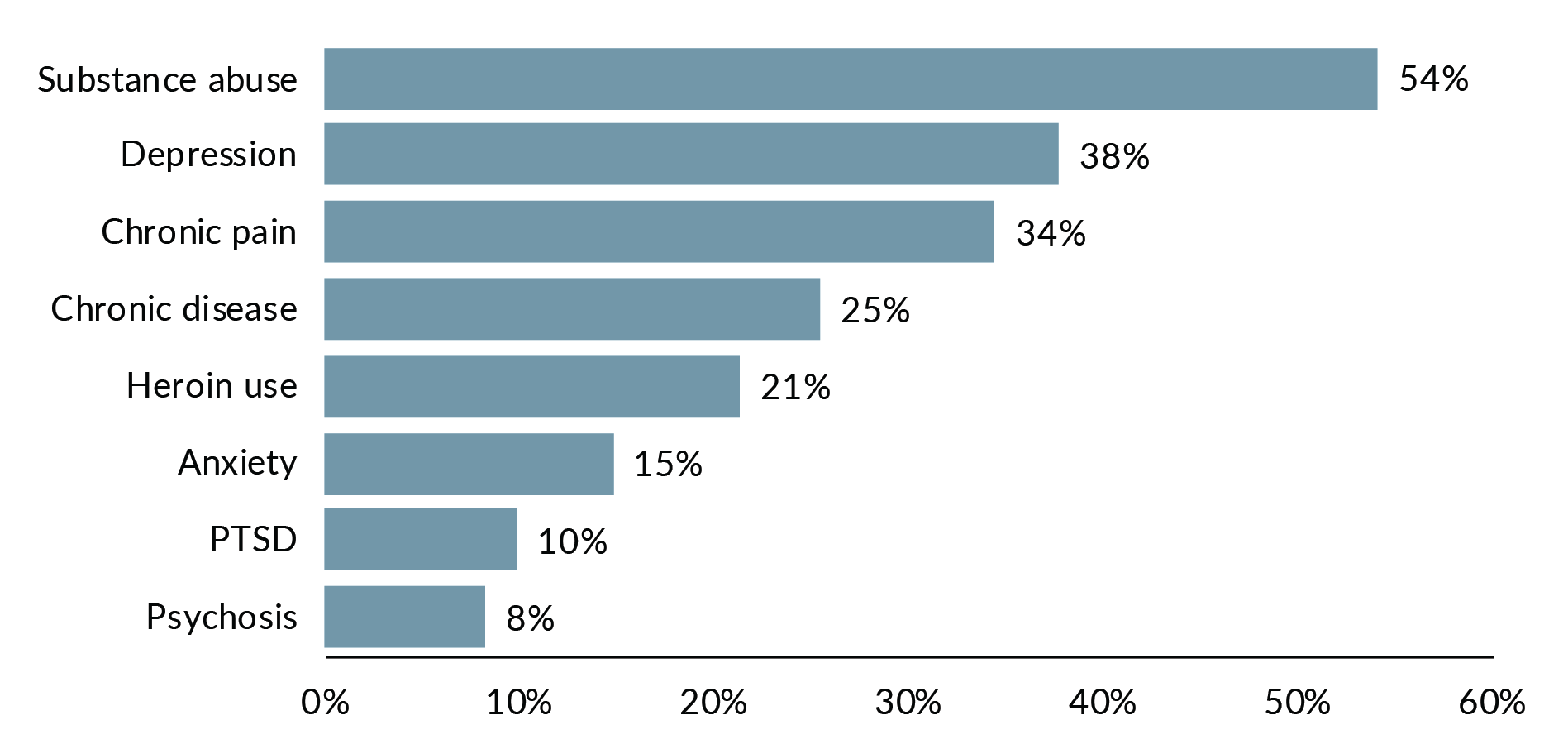

- Interviewers found high rates of poor physical and mental health including very high rates of substance abuse, mental illness, and chronic pain or disease (Figure 6). The interviews suggested that many of these challenges were linked to experiences of childhood trauma and exposure to violence.

- Participants experienced a deep level of material hardship in the first year after prison. Their median income in that first year was $6,000—enough to cover only two-and-a-half months’ rent for an average one-bedroom apartment.[15]

Source: B. Western, Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

Source: B. Western, Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

Participants who reported multiple physical or health problems were most likely to experience material hardship after leaving prison. Although joblessness declined over the course of the year for most participants, those with the most serious health issues were the least likely to become employed.

Policy/Practice

Evidence-Based Ways to Ease Reentry and Reduce Reoffending

Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers are looking for alternatives to high incarceration and for effective ways to reduce the chances that ex-prisoners return to crime and prison. Some examples of these efforts are explored below.

The Growth of Incarceration in the U.S. Consensus Committee

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) appointed a committee of experts in criminal justice, the social sciences, and history to review research on incarceration. The committee was charged with exploring its causes and consequences, especially for families and children as well as former prisoners, and with developing evidence-based recommendations. The resulting report, released in 2014, was entitled The Growth of Incarceration in the United States.[16]

The report suggests the following practical policy steps to lower the high incarceration rate in the U.S.:

- Reexamine long sentences, mandatory minimum sentences, and policies on enforcement of drug laws.

- Prepare incarcerated men and women to re-enter society.

- Reduce unnecessary harm to the families and communities of the incarcerated.

U.S. Department of Justice on Easing Reentry

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) notes that over 10,000 ex-prisoners are released from America’s state and federal prisons every week, and approximately two-thirds of them will likely be rearrested within 3 years of release.

The release of ex-offenders into communities represents a variety of challenges. Most often, prisoners are returning to impoverished and disenfranchised neighborhoods with few social supports and persistently high crime rates.

The DOJ identifies the following as the three key elements of successful reentry into communities that benefit both ex-offenders and the community:

- Help ex-prisoners find and keep employment;

- identify transitional housing; and

- provide mentoring.[17]

Life After Prison, the Boston Reentry Study

Bruce Western, Bryce Professor of Sociology and Social Justice and Co-Director of the Justice Lab at Columbia University, suggests that neither the police, nor the courts, nor the threat of punishment create public safety. Instead, establishing and maintaining bonds of community produced by families, schools, employers, and churches and other community organizations reduces crime and creates public safety.

Western calls for systems-level change, and cites numerous innovative programs that are helping individuals avoid prison or transition from prison to civilian life. Below are three such programs, which are highlighted in his book, Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison:

- Roca, Massachusetts: A youth antiviolence program that works successfully with youths who have been involved in serious violence to disrupt the cycle of incarceration and poverty. Of the 900 young men served in 2019, 278 were placed in jobs and 64% stayed in their job for a year or more.

- ComALERT, Brooklyn, New York: Supports adults who are transitioning from federal, state, or city incarceration back into their community. An evaluation found that clients were 15% less likely to be arrested again after 2 years than a control group with similar criminal history who didn’t participate in ComALERT.

- Transitions Clinic Network: A national network of medical clinics that provide comprehensive care for people recently released from incarceration who have chronic diseases. Each clinic employs a formerly incarcerated community health worker on the clinical team.

Citing research suggesting a close connection between high incarceration rates and the harsh conditions of poverty in the U.S., Western suggests that meaningful criminal justice reform will need to account for this reality, both in its policy specifics and in its underlying values.

Rethinking Reentry Report

In Rethinking Reentry[18], editor and coauthor Brent Orrell—an American Enterprise Institute resident fellow who served in the U.S. Departments of Labor and Health and Human Services—brings together leading academics, researchers, and criminologists to improve our understanding of what is working, and what isn’t, when it comes to improving outcomes for people returning to society from prison.

The report explores new approaches to serving ex-prisoners, including:

- Providing services based on an individual’s level of risk and needs;

- Conducting more and better qualitative research to tell the story of reentry from the perspective of the returning individuals and their families, as well as from the police, corrections personnel, and community supervision authorities;

- Exploring the potential use of prison-based therapeutic communities in reducing a return to crime;

- Considering the role of “identity change” in preventing future criminal behavior; and

- Using best-practices in program design and implementation to restore personal agency (a sense of having power over one’s life) for reentering citizens.

Edited by Deborah Johnson

Notes

[1] U.S. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016.

[2] B. Western, “Poverty, Criminal Justice, and Social Justice,” Focus 35, No. 3 (November 2019).

[3] Western, “Poverty, Criminal Justice, and Social Justice.”

[4] The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, National Research Council Committee on Law and Justice, National Academy of Sciences, April 2014.

[5] See “Mass Incarceration and Prison Proliferation in the United States,” Focus 35, No. 3 (November 2019). See also B. Western and B. Pettit, “Incarceration & Social Inequality,” Daedulus, Summer 2010: 8–19; See also, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences, National Research Council Committee on Law and Justice, National Academy of Sciences, April 2014; and B. Western, Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison (New York: Russell Sage Press, 2018).

[6] B. Pettit, B. Sykes, and B. Western, “Technical Report on Revised Population Estimates and NLSY79 Analysis Tables for the Pew Public Safety and Mobility Project” (Harvard University, 2009).

[7] Having a Parent Behind Bars Costs Children, States, Pew Charitable Trusts, Stateline article, May 24, 2016.

[8] See, for example, National Research Council, “Consequences for Families,” issue brief, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States, September 2014.

[9] National Research Council, “Consequences for Families.”

[10] D. Pager, “The Mark of a Criminal Record,” American Journal of Sociology 108, No. 5 (2003): 937-975.

[11] National Research Council, “Consequences for Families.”

[12] National Research Council, “Consequences for Families.”

[13] U.S. Department of Justice, Prisoners and Prisoner Re-Entry, n.d.

[14] B. Western, Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison, New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

[15] Estimates obtained from Renthop.

[16] The Growth of Incarceration in the United States.

[17] U.S. Department of Justice, Prisoners and Prisoner Re-Entry.

[18] B. Orrell, ed., “Rethinking Reentry,” Washington, D.C., American Enterprise Institute, January 2020..

Categories

Child Development & Well-Being, Children, Health, Health General, Homelessness, Housing, Housing Market, Incarceration, Inequality & Mobility, Justice System, Prisoner Reentry, Racial/Ethnic Inequality

Tags

Cross-National Comparison, Disability, Qualitative Research, Race/Ethnicity, Substance Abuse (or Alcohol/Drug Abuse)