Feature

Revised June 2021 | No. 5-2020

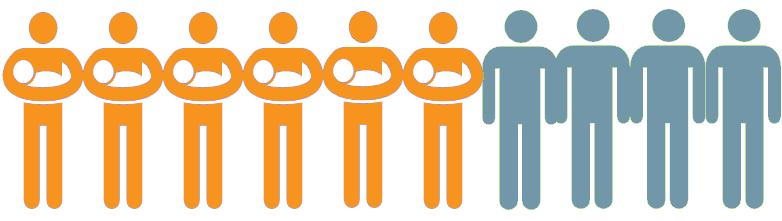

More than 72 million men in the United States have at least one biological child. That’s 60 percent of all men in the country. Some are married or cohabiting, while others are single parents or have recombined with another partner. There are also men who fill the role of father even though they’re not legally recognized as such.

Source: L. M. Monte, “Fertility Research Brief,” Current Population Reports, P70BR-147, March 2017.

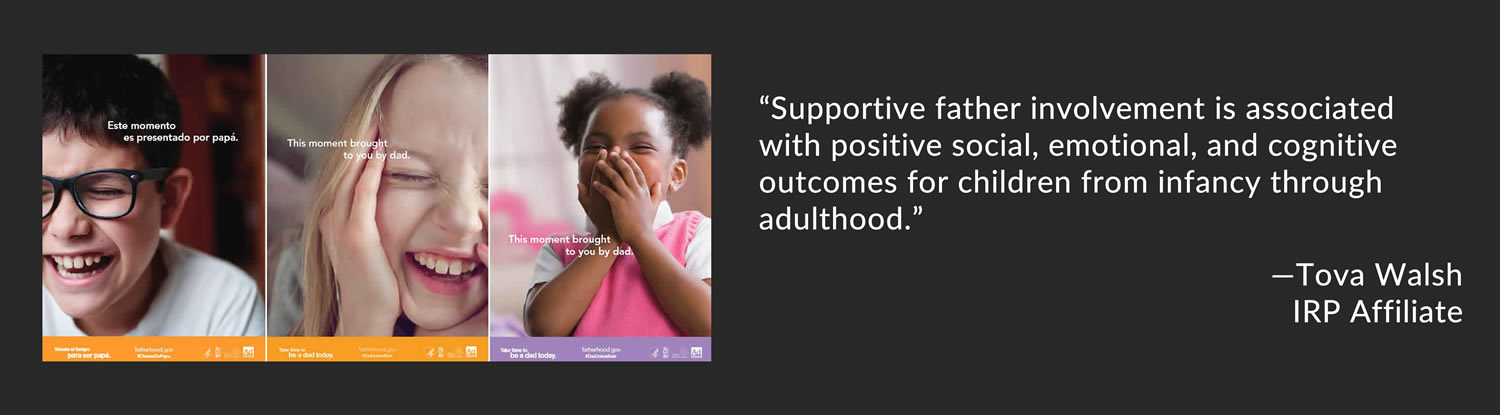

Involved fathering is sensitive, warm, close, friendly, supportive, affectionate, nurturing, encouraging, comforting, and accepting. It is associated with positive effects on children beginning even before birth. Fathers themselves also benefit from caring involvement in their children’s lives.

After their child’s birth, involved fathers are associated with

- children’s higher academic achievement;

- greater school readiness;

- stronger math and verbal skills;

- greater emotional security;

- higher self-esteem;

- fewer behavioral problems; and

- greater social competence than is found among children who lack a caring, involved father.

Growing evidence linking involved fathers with benefits for children has led policymakers, pediatricians, child support agencies, and family-services practitioners to step up their efforts to support and encourage fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives.

Policy/Practice

Table. How policymakers and service providers can support and encourage positive father involvement.

Table. How policymakers and service providers can support and encourage positive father involvement.

| Policymakers |

Provide paid paternal leave to allow fathers to stay home and bond with their infants and care for sick children.

Fund public-service announcements promoting positive, involved fathers and modeling effective coparenting relationships.

|

| Pediatricians |

Involve fathers in health care discussions during appointments.

|

| Social service providers |

Improve “father-friendliness” of programs and help fathers take stock of what they are doing for their children and where they could do more.

Encourage positive coparenting to help facilitate nonresident father involvement with their children.

|

| Child support caseworkers |

Inquire about noncustodial fathers’ barriers to spending time with their children and offer to help facilitate visits.

|

| Home-visiting providers |

Engage fathers in programming, either in concert with or separate from maternal home visits (see below).

|

Father Engagement in Home Visiting: Benefits, Challenges, and Promising Strategies. National Home Visiting Resource Center Research Snapshot Brief, James Bell Associates and Urban Institute

Research identifies the following challenges in engaging fathers in home visiting and promising practices to address these challenges:

Challenges

- Misperception that home visiting is just for mothers

- Staff resistance to including fathers and inadequate training

- Maternal gatekeeping and mothers wanting to keep home visits private

- Relationship and safety concerns especially when there is a history of intimate partner violence

- Scheduling conflicts when finding times for both parents

Strategies

- Assure that recruitment, enrollment, and outreach is father-friendly

- Use flexible scheduling practices

- Implement staffing practices that involve fathers, like hiring male staff

- Tailor program content and delivery for fathers

Trauma-Informed Approaches for Programs Serving Fathers in Re-Entry: A Review of the Literature and Environmental Scan, U.S. HHS OPRE Report #2018-69

Key findings from a review of evidence on trauma among fathers in re-entry and trauma-informed responsible fatherhood programs include:

- Trauma is prevalent among fathers who are re-entering society

- Trauma may complicate the experience of men in fatherhood programs

- Implementing a trauma-informed program requires an organization-wide trauma-informed approach

- All staff must be trained to recognize and respond to signs of trauma

- Programs should screen all participant for signs of trauma and refer fathers to gender and culturally appropriate services