- June 2021

- Fast Focus Policy Brief No. 53-2021

People who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) have higher rates of poverty compared to cisgender (cis) heterosexual people, about 22% to 16% respectively. But within that data, there are significant differences in the poverty rates of various subgroups depending on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI), as well as the intersection with other factors like race, age, and disability status. The Pathways to Justice Project of the Williams Institute in the UCLA School of Law seeks to compile, analyze, and interpret both qualitative and quantitative data on how LGBT people experience poverty.

Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey are the basis for “LGBT Poverty In The United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups,[1]” a report authored by M. V. Lee Badgett, Ph.D., Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Distinguished Scholar at the Williams Institute, and Bianca D.M. Wilson, Ph.D., Senior Scholar of Public Policy at the Williams Institute and Principal Investigator of the Pathways to Justice Project. This survey used a module of SOGI questions in 35 states from 2014 to 2017 and provides insights into the lived experiences of people who are cisgender straight men and women, cisgender gay men and lesbian women, cisgender bisexual men and women, and transgender people. By comparing poverty rates within those SOGI groups and overlaying that data with other demographic factors, a more complete picture of LGBT poverty in the United States emerged than has been possible before.

Many of the findings are not surprising in that they reflect patterns of poverty among straight people as well: women tend to be poorer than men, and people of color are generally more likely to be poor than their White counterparts. But with a deeper dive into SOGI subgroups, the variety of experiences becomes clear, including that overall, cis gay men tend to fare better financially than members of other SOGI groups. Alternately, cis bisexual women are closest to trans people in experiencing the highest rates of poverty regardless of other demographic characteristics.

Viewing poverty through the lens of SOGI, three distinct clusters emerge. Cis gay men have the lowest overall poverty rate (12.1%), with cis straight men only slightly higher (13.4%). Cis straight women, cis lesbian women, and cis bisexual men comprise a second group at 17.8%, 17.9% and 19.5%, respectively. And a marked jump in poverty rates exists among cis bisexual women and transgender people, both experiencing an average poverty rate of 29.4%.

It is important to note that the sample size for transgender people was too small to further differentiate between trans men, trans women, and gender nonconforming trans people in a statistically meaningful way. But the poverty rates for these groups do differ, with trans men at 33.7%, trans women at 29.6%, and gender nonconforming people at 23.8%.

Rates of poverty at the intersection of SOGI and other demographic factors

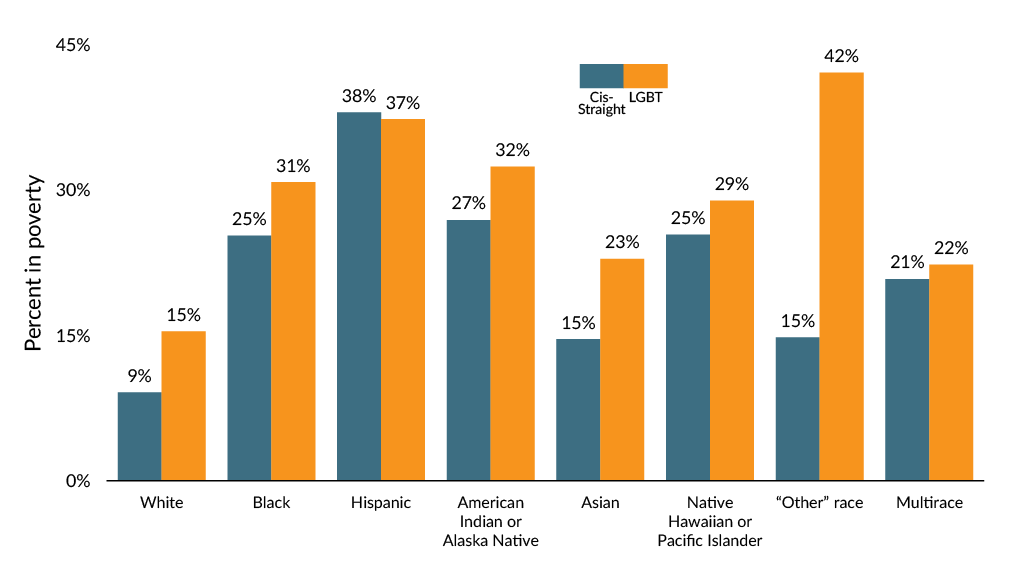

Race and SOGI

M., 32, African American and Cuban, LA, bisexual cisgender woman

“Maybe if my skin complexion portrayed myself as White, then, a lotta things would be different. I probably still have my kids if that was the case.”[2]

Race is a key indicator of economic hardship in the United States, and cisgender straight men and women are more likely to be White than their LGBT counterparts: 66% to 61% respectively. As noted above, except for cis gay men, people who identify as part of an SOGI group other than cisgender and straight are more likely to experience poverty. Coupled with the higher rates of poverty among people of color, when someone is both part of a sexual minority group and is a person of color, they have a much higher chance of living in poverty compared to both White counterparts and cis straight members of their own ethnic or racial group.

Source: Data is from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey 2014–2017.

Notes: All race/ethnic groups are mutually exclusive. The “Other” race category represents respondents who did not select any of the racial groups on the BRFSS and also did not select Hispanic (e.g., “Other, Non-Latinx/Hispanic”) and is exclusive of respondents selecting “Don’t know” or “Refused.”

Age and SOGI

The rates of poverty for both cis straight people and for members of SOGI minority groups tend to follow similar patterns—rates are highest for the youngest group (18–24 year-olds), decline slightly in the next two tiers (ages 24–34 and 25–44), and then continue to fall for those 45–54 and 55–64, with the lowest rates for those 65 and older. While there is some variance within SOGI groups that differs from typical poverty rates when age is not considered, some factors remain true—cis gay men are closer to cis straight men than they are to other SOGI groups, cis women are similar regardless of whether they are lesbian or straight, and transgender people have the highest likelihood of living in poverty in any age range.

It is important to note that young people who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender can be particularly vulnerable to poverty due to risks of family rejection and its consequences. They may end up homeless, couch surfing, or in foster care, all of which can make finishing high school difficult, and are predictors of future poverty. Those challenges are further intensified for young people of color.

Health, ability and SOGI

Having a disability is another major risk factor for poverty in the United States. U.S. Americans living with a disability are more than twice as likely to live in poverty than their currently able-bodied counterparts[4]. And while only about 12% of the U.S. working-age population is living with a disability, they represent more than half of those living in long-term poverty.

The correlation between disability and poverty is significant because LGBT people are more likely to be living with a disability than cis straight people. In the BRFSS data, cisgender straight men have the lowest disability rate at 19.5%, followed by 24.3% for cis straight women. By comparison, 28.4% of gay and bisexual men and transgender men reported living with a disability, as did 35.4% of lesbian and bisexual women and transgender women.

Camila, 24, Latinx, LA, bisexual trans woman

“I’ve been denied jobs before because I’m trans, and I think it’s affected me emotionally to the point where even if I didn’t have a physical disability, I don’t think that mentally I’m prepared to work because of all of the things that I’ve been through related to me being trans. And it’s not because I’m transgender. It’s because other people’s perceptions need to change. And, you know, people need to start minding their business and being more accepting.”[3]

Although it is unclear why more LGBT people are living with a disability, the implications for the risk of poverty are clear. One potential clue about the elevated disability rate among LGBT people can be found in the BRFSS survey’s questions about health. When asked to evaluate the condition of their health, cisgender straight women had the most positive assessments, with only 18.2% rating it as just fair or poor. This is in comparison to an overall fair or poor rating of 22.3% for other female-identifying sexual minorities, including cisgender lesbians (17.7%), cis bisexual women (23.4%), and transgender women (24.9%).

On the other hand, cisgender gay men reported the most positive health assessments, with just 13.9% rating their health as only fair or poor. They were followed by cis straight men (16.7%), cis bisexual men (20.7%), and transgender men (24.9%).

SOGI and the experience of childhood poverty

Another component of the Pathways to Justice Project is a report detailing the lived experience of LGBT people in poverty[5]. Many of the accounts illustrate similar data points and correlations outlined above. But one connection that had not emerged in the quantitative analysis arose in the interviews: the high likelihood that LGBT people living in poverty as adults had also experienced childhood poverty. In fact, 73% of the respondents, 97% of whom identified as a SOGI minority, reported having lived in poverty early in life. Segmented by race and ethnicity, it became clear that LGBT people of color who were poor as adults were very likely to have experienced family poverty as children. In fact, more than 4 out of 5 Black, Native American, and Latinx interviewees shared memories of economic insecurity as children, compared to about half of White and Asian American/Pacific Islander respondents.

Cori, 48, Black/African American, Los Angeles, gay nonbinary

“Gosh. We got a lot of food through churches. … Grew up on welfare, a lot of bread. My mom knew how to make things stretch. She learned how to make, you know, Hamburger Helper, stuff like that, make it all stretch by adding the stuff to it. … We didn’t have a lot of toys. We didn’t have a lot of things. We didn’t have a lot of clothes, but my mom would hustle to have enough food in the house. So she would go to one, two, at least four food banks I know of.”[6]

For the LGBT adults living in poverty who did not grow up poor, other conditions were at play that started their pathway into poverty. In their interviews, those respondents reported other risk factors including substance abuse and mental health issues; anti-LGBT attitudes at home, work or school; and becoming a parent at a young age without community or familial support.

Conclusion

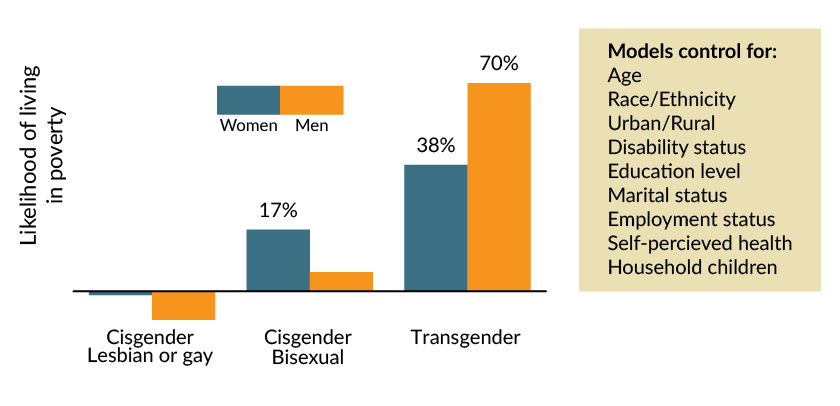

Source: Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey 2014–2017.

Notes: Figures represent the odds ratio (product of logistic regression models) of living in poverty compared to straight, cisgender respondents. Percentages indicate statistical significance (p<.05).

While many demographic factors can either decrease or increase the likelihood of living in poverty, overall, people who identify as LGBT are more at risk of being poor. Within that group, however, there are large variations depending on to which SOGI subgroup a person belongs.

Cisgender gay men face a similar risk of living in poverty compared to their cisgender straight counterparts when other demographic features are similar. This is also true when comparing cis straight women and cis lesbians. Bisexual men appear to have a higher risk of poverty but that disappears when other factors are considered. Transgender people and bisexual women, on the other hand, are consistently most at risk of experiencing poverty across the lifespan.

Progress in reducing poverty within the LGBT community involves addressing specific factors which tend to protect people from the risk of economic hardship. While not guarantees, protective factors include being employed, attaining higher levels of education, living in a more urban area, being married, not growing up in poverty, not becoming a parent at a young age, and having access to quality health care. Research and implementation of policy and cultural changes can help to ensure that LGBT people have the same opportunities to thrive as their cisgender straight counterparts.

[1]Badgett, M.V.L and Wilson, B.D.M. (2019). LGBT Poverty In The United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups. Institute, UCLA School of Law.

[2]Wilson, B.D.M. and Badgett, M.V.L. (2020). Pathways Into Poverty: Lived experiences among LGBTQ people.

[3]Wilson and Badgett (2020). Pathways Into Poverty: Lived experiences among LGBTQ people.

[4]National Council on Disability. (2017). Highlighting Disability / Poverty Connection, NCD Urges Congress to Alter Federal Policies that Disadvantage People with Disabilities.

[5]Wilson and Badgett (2020). Pathways Into Poverty: Lived experiences among LGBTQ people.

[6]Wilson and Badgett (2020). Pathways Into Poverty: Lived experiences among LGBTQ people.

Categories

Child Poverty, Children, Employment, Employment General, Family & Partnering, Family & Partnering General, Health, Health General, Inequality & Mobility, Racial/Ethnic Inequality