- Robert A. Moffitt and James P. Ziliak, edited by Mitchell McFarlane

- April 2021

- Fast Focus Research/Policy Brief No. 52-2021

As COVID-19 has caused an economic downturn in the United States, more Americans have relied on safety-net programs. Our recent work examines how well the safety net in the United States responds to recessions such as that resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] We combine annual survey data from 2001 to 2019 with weekly surveys conducted in 2020 to provide a picture of the labor market and safety net over the past twenty years. This research shows that the COVID-19 recession has been severe, with the employment-to-population ratio experiencing a sharper drop than in the Great Recession, and with low-income households and less skilled workers experiencing the steepest declines in employment.

Few programs in the United States are set up in a way that allows them to provide more generous support during economic downturns. Over the past two decades, only unemployment insurance and food assistance have significantly expanded in response to employment losses. We propose several changes to the safety net that would make it more responsive to future recessions.

Most Programs Are Not Designed to Respond to Economic Downturns

Social safety net programs in the United States can be classified as either social insurance or means-tested transfers. Social insurance programs—such as Social Security—are generally tied to employment or old age and were not designed to help people affected by recessions. Means-tested programs, which are intended to help provide support to those with low incomes, should be expected to expand during times of high unemployment.

However, most means-tested programs in the United States are not designed to operate in this way. Housing assistance and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) are not entitlements—that is, not everyone who meets the program eligibility criteria is legally entitled to receive benefits—and funding for these programs is fixed and does not meet demand. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is only available to people who are disabled, blind, or aged 65 or older. Medicaid eligibility has historically been restricted to those with young children, disabled people, and the elderly. While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 permitted states to expand eligibility to childless adults, only about three quarters of states have chosen to do so. Workers must wait to receive the Earned Income Tax Credit annually, and, for those who are laid off or had their earnings reduced to low levels, the size of the credit may be lower than it would have been in the absence of a recession.[2]

Only two programs—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called the Food Stamp Program) and Unemployment Insurance (UI)—provide substantial income support during economic downturns. SNAP comes closest to being an automatic economic stabilizer. The program provides nearly universal eligibility to low-income Americans and is an entitlement program, so all who are eligible are entitled to benefits. SNAP has work requirements for able-bodied adults with dependents, but this requirement can be waived in areas with high unemployment.

UI is specifically designed to help the unemployed, and, in times of high unemployment, the maximum length of benefits may be expanded. However, independent contractors, the self-employed, people with short work histories, and those who work part time have not historically been covered by UI. And, since individual states must pay UI benefits using their own trust funds or by borrowing from a federal account, they often cut benefits or restrict eligibility following recessions in an effort to restore their fund balance and repay loans.

- Social Security Retirement and Survivors Benefits

- Disability Insurance

- Medicare

- Unemployment Insurance*

- Medicaid*

- Supplemental Security Income (SSI)*

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)*

- Housing assistance

- Child care subsidies

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)*

- Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)

- Child Tax Credit (CTC)

Comparison of government response to downturns caused by the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic

While there are always Americans who need assistance for a variety of reasons, there are also times of crisis in which a much larger portion of the population finds itself struggling. While parts of the safety net are designed to, or at least be capable of, expanding to meet those needs, policy decisions determine which programs are adjusted, and for whom and how much those supports are increased.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Great Recession from approximately 2007–2011 was the most recent period during which safety net programs were called on to expand in a significant way. Our research finds that previous and current approaches for some of the programs differ in important ways. For example, during the Great Recession, legislation passed by Congress temporarily expanded a variety of benefits, including:

- lengthening the amount of time that UI could be accessed;

- increasing the amount of SNAP benefits, housing assistance, child-care funds and TANF payments;

- offering EITC benefits to more families; and

- boosting the share of Medicaid payments paid for by the federal government.

In addition to these provisional expansions, there was also a temporary payroll tax deduction created, and people receiving Social Security and Disability benefits received a one-time cash payment. These efforts were targeted towards people living in lower income brackets, and the cumulative effect was to prevent any rise in the poverty rate in the early part of the Great Recession.

The policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been narrower because fewer programs have been expanded, but deeper in those that did increase. For example, SNAP benefits were increased, but only for recipients who were below the maximum benefit, until recently when the maximum was temporarily increased by 15 percent for the remainder of the federal fiscal year. Federal Medicaid subsidies and rental assistance via housing vouchers each increased by only 6 percent, less than in the Great Recession. And EITC, TANF, SSI and subsidized housing programs have, for the most part, not been adjusted to address current increased needs.

The COVID-19 response has exceeded the Great Recession approach in two significant ways. First, cash payments for which the vast majority of Americans qualified were disbursed first in 2020 and again in 2021 with minor changes to amount and eligibility. This included cash allowances for each child in a family in addition to payments for each adult. Equally, if not more importantly, Congress temporarily provided major additional support to the UI program by providing significant weekly supplements to UI recipients. They also expanded the number of weeks benefits could be received, and extended coverage to the self-employed, independent contractors, and gig and part-time workers.

For Most Safety Net Programs, Participation Does Not Significantly Increase in Response to Recessions

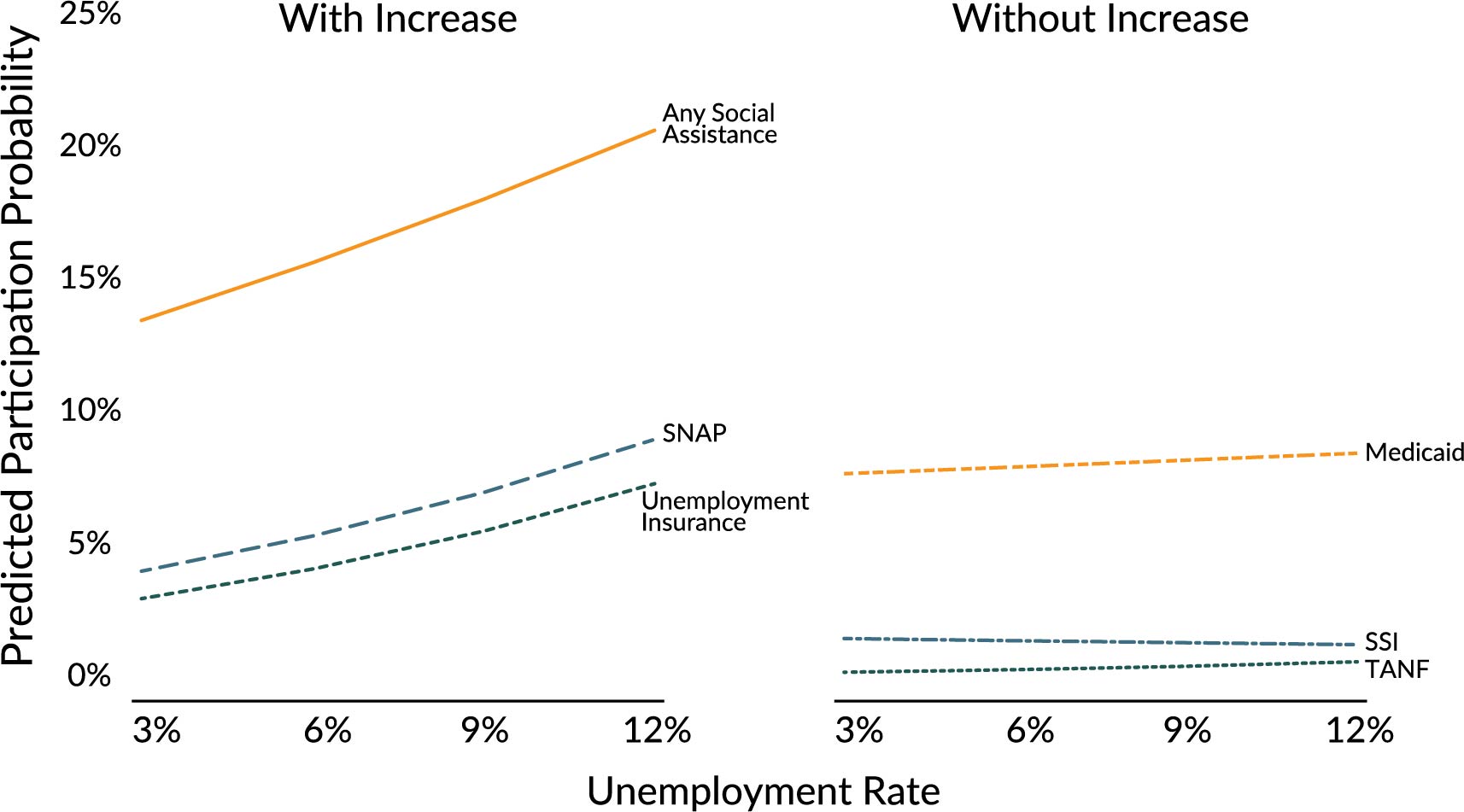

We analyzed how program participation changed over the past two decades for five programs: Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, SSI, and UI. In particular, we examined the degree to which program participation increased during times of high unemployment. Only SNAP and UI have grown significantly in response to increases in unemployment over the past 20 years (see Figure 1.) and these were the two programs that have provided the most support to people during the COVID-19 recession.

Source: This graph illustrates the authors’ calculations of 2001–2019 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement and Weeks 1–3 of Covid Impact Survey. Any Social Assistance includes Unemployment Insurance (UI), Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Results show the effect of changing the unemployment rate on the predicted probability of participation holding other variables at their mean values.

We also note that overall program participation experienced “secular” growth—growth beyond that due to changes in the economy. This secular growth was driven largely by Medicaid, which saw participation rates triple over the past two decades. SNAP experienced more modest secular growth. Participation rates for TANF and SSI, in comparison, remained mostly flat throughout the time period, and UI saw large fluctuations that were attributable to changes in the business cycle, especially over the Great Recession and COVID-19 pandemic.

Several Reforms Could Make the Safety Net More Responsive to Future Economic Downturns

In light of findings that the U.S. safety net does not adequately respond to times of high unemployment, we propose a number of reforms that would allow safety-net programs to better respond to future recessions.

Several modest changes to SNAP and UI could make them better automatic stabilizers.

For SNAP, we suggest:

- automatically removing work requirements for able-bodied adults with dependents in times of high unemployment, rather than leaving this to state discretion to request a waiver from federal rules;

- raising the asset limit and automatically suspending it during recessions to capture more middle-class families with savings;

- extending the recertification period for households with earnings to at least six months during downturns; and

- automatically increasing the maximum benefit during downturns.

For UI, changes include:

- using federal funds to fully pay for additional weeks of benefits during downturns;

- increasing the floor for minimum unemployment insurance benefits (while subsidizing states with low tax bases to help them pay for this expansion);

- permanently extending coverage to part-time and self-employed workers and independent contractors, possibly at a price; and

- providing subsidies to states to update outdated information technology systems that may delay UI payments.

We also suggest more extensive reforms to TANF and Medicaid that would allow these programs to become automatic stabilizers.

For TANF, we recommend:

- using federal funds to automatically increase cash assistance during downturns; and

- suspending time limits and work requirements during recessions.

We also suggest automatically increasing the share of Medicaid expenses paid by the federal government to encourage states that have not yet done so to expand Medicaid coverage under the ACA.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed limitations of the safety net. While safety-net programs have helped many people during economic downturns, most programs do not expand to meet increased need during recessions. In the COVID-19 recession, only UI and SNAP have expanded significantly in response to a massive increase in unemployment. Reforming safety-net programs so that they automatically expand during recessions would allow the programs to serve people better while alleviating the need for ad hoc legislation during economic downturns.

[1]Moffitt, R.A. and Ziliak, J.P. 2020. “COVID-19 and the U.S. Safety Net.” Fiscal Studies, 41(3): 515–548. Cross-listed as NBER Working Paper No. 27911.

[2]Larrimore, J., Mortenson, J., and Splinter, D. 2016. “Income and Earnings Mobility in U.S. Tax Data,” in Economic Mobility: Research & Ideas on Strengthening Families, Communities & the Economy, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 481–516.

Categories

Economic Support, Employment, Food & Nutrition, Food Assistance, Housing, Housing Assistance, Means-Tested Programs, Social Insurance Programs, Unemployment/Nonemployment

Tags

COVID-19, Great Recession, Medicaid, National, Pandemic Relief (CARES Act), SNAP/Food Stamps, Unemployment Insurance (UI)